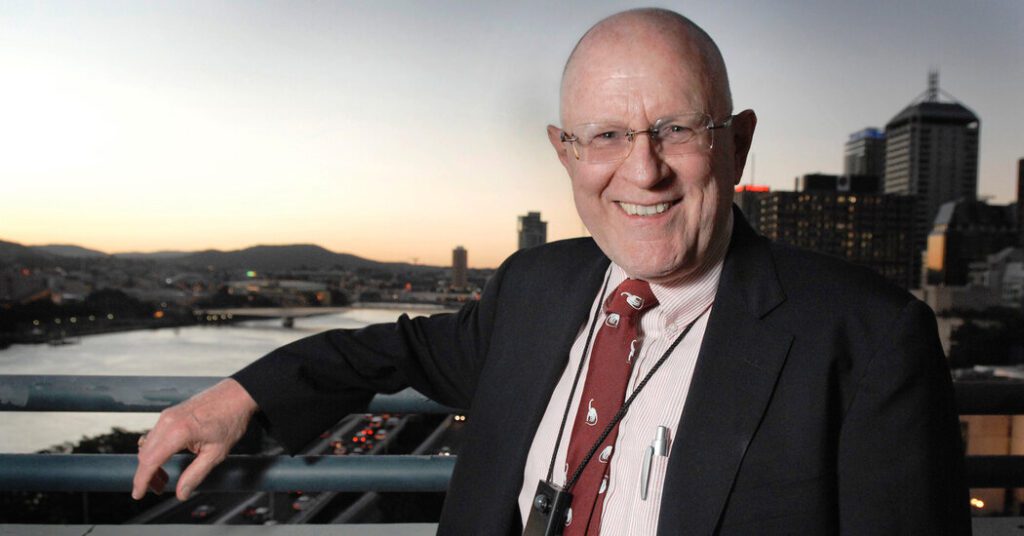

C. Gordon Bell, the technology visionary whose Digital Equipment Corporation computer designs helped spur the emergence of the minicomputer industry in the 1960s, died Friday at his home in Coronado, California. He was 89 years old.

The cause of death was pneumonia, the family said in a statement.

Dubbed the “Frank Lloyd Wright of computers'' by Datamation magazine, Bell was a master architect in the effort to create smaller, more affordable interactive computers that could be clustered into networks. Computers Mr. Bell, who was a master of architecture, built the first time-sharing computers and led the effort to build the Ethernet. He was one of the few influential engineers whose designs served as an important bridge between the room-sized model of the mainframe era and the advent of personal computers.

After working at several other startups, he became head of the National Science Foundation's Computer and Information Science Engineering Group, where he led efforts to link the world's supercomputers into high-speed networks that led to the modern Internet. directly led to the development of He then joined Microsoft's early research labs, where he remained for about 20 years before being named a research fellow emeritus.

He was awarded the National Innovation Medal in 1991.

“Bell's greatest contribution was his vision for the future,” said David Cutler, a senior technical fellow at Microsoft Research and a leading software engineer who worked with Bell at both Digital and Microsoft. talk. “He was always envisioning the future of computing. He helped make computing broader and more personal.”

At a time when computer companies like IBM were selling multi-million dollar mainframe computers, Digital Equipment Corporation, founded and run by Kenneth Olsen, wanted to introduce small, powerful machines that could be bought for a fraction of the cost. Hired in 1960 from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology campus as the company's second computer engineer, Bell designed all of the products that were early entrants into what was then called the minicomputer market.

The PDP-8 was a 12-bit computer released in 1965 at a price of $18,000 and was considered the first successful minicomputer on the market. More importantly, Digital Equipment Corporation's minicomputers were sold to scientists, engineers, and other users who interacted directly with machines at a time when corporate computers were off-limits to such users. It was stored in a glass-walled data center under the supervision of experts.

“All DEC machines were interactive, and we believed that people could talk directly to the computer,” Bell said in a 1985 interview with the industry publication Computerworld. In this way, Mr. Bell foresaw the coming personal computer revolution.

Under the often autocratic Mr. Olsen, the company was an engineering-oriented environment where product lines drove the business, consensus was formed after loud and often acrimonious debate, and a matrix-like structure defined the boundaries of management. It was blurring the lines. This controlled chaos was a source of great stress for Mr. Bell. Much to Bell's chagrin, he often clashed with Olsen, who was known to keep an eye on the engineers' work.

Uneasy, Mr. Bell took a six-year leave to teach at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, but returned to the company in 1972 as vice president of engineering. Reinvigorated and full of new ideas, he supervised the design. A completely new computer architecture. His VAX 780, a fast, powerful, and efficient minicomputer, was a huge success, sales increased, and by the early 1980s, DEC was the world's second-largest computer manufacturer.

“Gordon Bell was a giant in the computer industry,” said Howard Anderson, founder of the Yankee Group, a technology industry research firm that tracked the market at the time. “I think DEC's success is due as much to him as it is to Ken Olsen. He believed that engineering talent came first, and he attracted the best engineers in the industry to DEC, and it became a thriving place.”

At DEC, tensions between Mr. Olsen and Mr. Bell once again became unbearable. Stressed by the pressure to continue producing winners and Olsen's overbearing presence, Bell quickly became angry (he was known to throw erasers at people during meetings). This angered and confused the engineers. In March 1983, while on a ski trip to Snowmass, Colorado, with his wife and some of the company's top engineers, Mr. Bell suffered a severe heart attack at the ski lodge, and without the efforts of Bob Puffer, he would have died. There might have been. The company's vice president revived him with CPR.

After several months of recuperation, he returned to work but decided it was time to retire for good. He resigned in the summer of 1983 after protests from several company executives.

Chester Gordon Bell was born on August 19, 1934 in Kirksville, Missouri, to Chester Bell, an electrician who owned an electronics store, and Laura (Gordon) Bell, an elementary school teacher.

He was diagnosed with a congenital heart condition at the age of seven and spent most of his second grade at home, mostly in bed. He spent his time confined to his home wiring circuits, doing chemistry experiments, and cutting puzzles with a jigsaw. After recovering, he spent countless hours learning about electrical repairs in his father's shop. By age 12, he had become a professional electrician, installing the first domestic dishwasher, repairing motors, and disassembling and rebuilding mechanical devices.

Mr. Bell graduated from MIT in 1957 with a master's degree in electrical engineering. He then won a Fulbright Scholarship to the University of New South Wales in Australia, where he developed and led the university's first graduate program in computer design. While there, he met fellow Fulbright scholar Gwen Druyo, whom they married in 1979 and founded the Computer History Museum in Boston in 1996. The two divorced in 2002.

Mr. Bell returned to MIT and pursued a Ph.D., but abandoned that pursuit and joined Digital Equipment Corporation. He had no interest in research and believed that an engineer's job was to create things.

After leaving the company, Mr. Bell became the founder of both Encore Computer and Ardent Computer. In 1986 he joined the National Science Foundation, delving deeper into the world of public policy and creating a supercomputer that led to the early stages of the Internet called the National Research and Education Network, where he led a networking effort. In 1987, he had the ACM Gordon sponsored his Bell Prize for research in parallel computing.

He eventually moved to California, where he became an angel investor in Silicon Valley and an advisor to Microsoft, which was opening its first lab in Redmond, Washington, in 1991. Bell joined the Microsoft Research Silicon Valley lab full time in 1995. There, he worked on MyLifeBits, a database designed to capture all of your life's information, including articles, books, CDs, letters, e-mails, music, home movies and videos, into a cloud-based digital database.

Mr Bell is survived by his second wife, Sheridan Sinclair Bell, whom he married in 2009. His son, Brigham, and his daughter, Laura Bell, were both from his first marriage. his stepdaughter, Logan Forbes; his sister, Sharon Smith; and four grandchildren.

In a 1985 Computerworld interview, Bell laid out his formula for repeating technological success: “The key in any technology is knowing when to jump on the bandwagon, when to push for change, and when to get off the bandwagon and get off,” he said.

Alex Traub Contribution report.