Mario Vargas Lurosa, a Peruvian novelist who portrayed gritty realism and playful erotica and the struggle for individual freedom in Latin America, while also writing an essay that became one of the most influential political commentators in the Spanish-speaking world, who passed away on Sunday in Lima. He was 89 years old.

His death was announced in a social media statement by his children.

Vargas Llosa, who won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2010, gained fame in Peru as a young writer with a crude and ferocious vision of corruption, moral compromise and atrocities. He joined a cohort of writers like Gabriel Garcia Marquez of Colombia and Giulio Cortazar of Argentina.

His dislike for the norms of Peruvian polite society gave him abundant inspiration. After he was registered at the Leon Cioprad Military Academy in Lima at the age of 14, Vargas Llosa transformed the experience into his first novel, Time of the Hero, published in 1963, an important account of military life.

The book was condemned by several generals, including those who claimed it was funded by Ecuador to undermine the Peruvian army.

However, Vargas Llosa was not completely engrossed in the magical realism of his contemporary era. And he was disillusioned with Fidel Castro's persecution of opposition in Cuba and broke from the ideology of the left that had been shaking for decades more than many Latin American writers.

He illustrated his own path as a conservative, often divided political thinker, and as a novelist who transformed episodes from his personal life into books that echoed far beyond the borders of his home country.

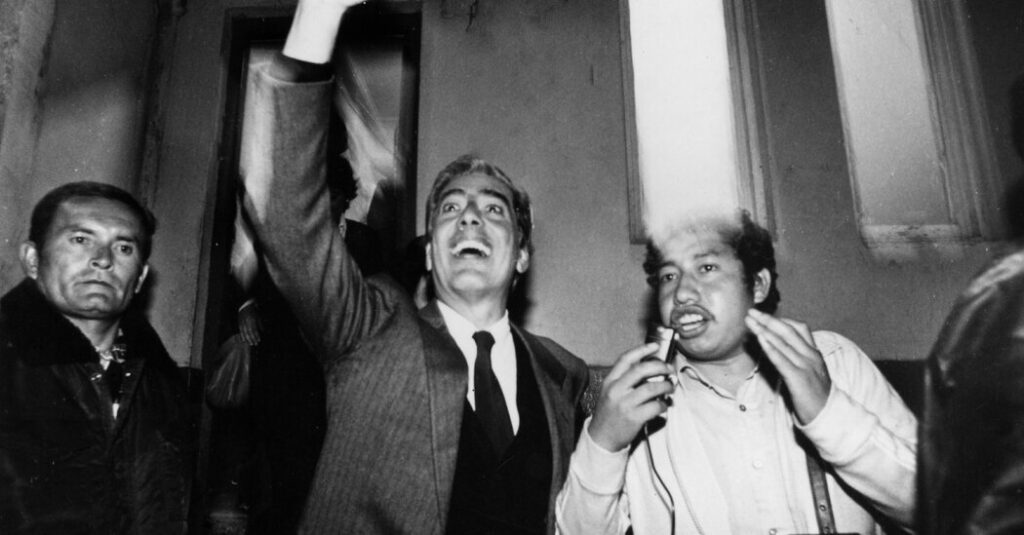

His hand in politics eventually took office in 1990. That race allowed him to defend the free market causes he supported.

He led the polls for most of the race, but was later defeated violently by Alberto Fujimori, a lesser-known Japanese agriculture scholar who adopted many of Vargas Lurosa's policies.

Vargas Llosa was passionate about fiction, but he began with journalism. As a teenager, he is a nighttime reporter for the daily Lima, Lachronica, documenting the world of dive bars, crime and prostitution. The elements of that experience were fed into the 1969 novel Conversation in the Cathedral. This depicts Peru's mal laziness under the military dictatorship of General Manuel Odolia in the 1950s.

And while he often wrote articles for European and American newspapers, Vargas Llosa experienced journalistic rebirth in the 1990s as a columnist for the Spanish newspaper El País.

His two-week column, “Piedra de Toque” or “Touchstone,” was syndicated in Spanish newspapers from Latin America and the US. It gave him a platform for topics like the reappearance of Andean populism, the art of Claude Monet and Paul Gaugin, and his raucous support for Israel.

The columns may be inspired by autobiographical or news events, and often by adjectives. They were written elegantly in a style that could reach readers who might not have had the patience to complete some of his long, intricately crafted novels.

“There are many venerable newspaper columnists in the United States, but who is Vargas Rosa's height in Hispanic civilizations?” Literary critic Iran Stavans wrote in an analysis of a 2003 column. “He is a polymer with eyes and ears everywhere, louder like thunder, lightly wearing his wisdom.”

Perhaps more than anything, this column allowed Vargas Lurosa to promote his ideas about how personal freedom depends on strengthening society based on free trade.

He often portrays what he departed on these principles of Latin America, and is ranked among the most prominent critics of the left governments of Venezuela and Cuba.

However, the idea of the free market had almost visceral appeal to him. When British conservative Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher resigned in 1990, she received flowers from Vargas Lurosa. He also said, “Madame: There are not enough words in the dictionary to thank you for what you did for the cause of freedom.”

That's what Jorge Mario Pedro Vargas Rurosa did. Born on March 28, 1936 in Arequipa, southern Peru, he spent most of his childhood in the Bolivian city of Cochabamba with his mother, Doralsa and grandparents. They created a modest means middle class family, but he was told that his father was dead.

His parents had actually separated a few months before he was born, so his father, Ernesto Vargas, who worked for the airline's Panagura, took the challenge abroad and demanded divorce from his wife.

They met again in Peru when their son was 10 years old. However, the boy, worn out by the discipline his father met, was soon sent to the military academy in Lima. After that experience, at age 19, Vargas Llosa eloped with Julia Urquidi Illanes, the sister-in-law of his 29-year-old uncle.

The marriage was turbulent, shocking his family, urging him to write “Aunt Julia and the Screenwriter.” Published in 1977, the book is one of his most famous novels translated into English, and describes the comedy struggles of Marito Balgitas, a young law student and aspiring author who falls in love with his aunt against the backdrop of radio soap opera.

Urquidi responded to a book detailing their thread bear and tension-filled years in Europe in an important memoir of time with Vargas Llosa, “What Varguitas Didn't Say.” They divorced in 1964, and Vargas Llosa married Patricia Llosa and had three children.

They split in 2015 after 50 years of marriage when they confirmed their romantic involvement with singer Giulio Iglesias' ex-wife, Isabel Preesler. He and Prissler were born in the Philippines and became famous socialites in Spain, separated in 2022.

He was survived by two sons, writer Alvaro and Gonzalo, the representative of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees. Her daughter, Morgana, a photographer.

Deciphering Peru ruled most of his job, but Vargas Lurosa lived abroad for a long time. In the 1960s, in Paris, he worked as a translator and achieved his goals by writing breaking news for Agence France-Presse. He later settled into a writing life in Barcelona before returning to Peru in the 1970s.

He gained greater fame as a novelist, but his 1990 presidential election emerged as a sort of surprise after writing an opinion essay denounced President Alan Garcia's plan to nationalize banks.

Just as Peruvians tackled hyperinflation, and bombing campaigns conducted by sparkling pass, Maoist guerrilla group Vargas Lurosa temporarily stopped writing fiction and formed his own right-wing party called the Free Movement.

His candidacy, inspired by political and economic philosophers in Europe and North America, and his brightly coloured skin, trim physique and his very appearance, which favors preppy sweaters, is in contrast to voters made up of poor Quechua-speaking people and Spanish-speaking mestizos.

Evoking his non-European ancestors, Fujino portrayed himself as an ally of the lower class long ruled by elite whites. Similarly, his opponents questioned whether Vargas Lurosa should rule after acknowledging that he was an agnostic.

He led polls for most of the race, but he was eventually beaten violently by Alberto Fujimori, a little-known agriculture scholar of Japan who adopted many of Vargas Lurosa's policies before disbanding Congress and unifying political power in his hands.

Disillusioned by his failed political advancement, Vargas Lurosa left Peru again in the early 1990s, splitting his time between London writing, with an apartment in Knightsbridge and a home in Madrid.

Disappointing many people in Peru, King Juan Carlos of Spain signed the royal laws in 1993, giving Vargas Lurosa Spanish citizenship.

In addition to the Nobel Prize, Vargas Llosa was awarded the Spanish Miguel de Cervantes Award in 1994 and the Jerusalem Award in 1995.

Some of his best works examined the whims of Latin American history. For example, “War at the End of the World” (1981) was a huge fictional account of the late 19th century Messianic movement in Canoe, a town located on a dry spread in northeastern Brazil.

Vargas Llosa researched the books in the Rio de Janeiro and Salvador archives and finished writing in 1980 at the Wilson Center in Washington that wasn't too far from the battlefield of civil war.

“I was surrounded by viewing distances on the flying falcon and the balcony where Abraham Lincoln spoke to his Union soldiers on the brink of the Battle of Manassas,” Vargas Lurosa wrote in the book's prologue.

But he could write elegantly everywhere, but for him he had a special charm that once wrote “doubt, passion, anger” and even “smeared with kindness.”

“I know Herman Melville called Lima the strangest and saddest city,” he told The New York Times in late 1989, referring to a passage from “Moby Dick.”

“Why?” Vargas Llosa said. “Fog and drizzle.”

He then laughed, “I don't know if fog and drizzle are big issues with Lima.”

Yang Zhuang and Elda Cantu Reports of contributions.