Sometime in the late 18th century, a sign outside a shabby butcher's hut in the English town of Stratford-upon-Avon read, using the then-common spelling of his name, “The immortal Shakespeare was born in this house.'' 'A sign appeared. The believers began their pilgrimage, kneeling, weeping, and singing the hymn: “May your temple be untouched and holy, Willie of Avon, God of the Bards!”

A merchant became wealthy selling carvings from local mulberry trees that looked like parts of real crosses. Some skeptics suspected the sign was part of a plan to bring tourists to Stratford. Others wondered if it had been hung by a resident of the estate. A local antiquities dealer criticized the whole scene as “a scheme to extort money from thoughtless and thoughtless people.”

Pilgrims flocked to the house and it became a place. The site is so sacred that one visitor warned that the worship of Shakespeare could overshadow the worship of God.

Yet, as reason weighs on us, a sigh escapes/Forget the fame given to Shakespeare/Those thousands of his admirers/Worship heaven!

Some 250 years after breaking away from the Catholic Church, England had its own Bethlehem and Manger.

Problem: No one actually knows where Shakespeare was born.

Mock Tudor and magic wand

Stratford-upon-Avon is located in the Midlands, two hours northwest of London, roughly in the center of England. Currently it is one of the most popular tourist destinations in the UK, visited by up to 3 million tourists a year. The birthplace is its main attraction, followed by the cottage reputed to be where Shakespeare's wife, Anne Hathaway, grew up.

Stratford has an Elizabethan kitsch vibe, with souvenir shops and half-timbered buildings. In the 19th century, as the Victorians tried to make Stratford seem more 'authentic', it became full of fake Tudors.

The town's economy and identity revolve around its Shakespeare craze, which culminates each year on April 23, Shakespeare's birthday. Conveniently, this day is also St. George's Day, which honors England's patron saint.

On my first visit in June 2021, I passed Hathaway Tea Room and a cafe called Food of Love, which had a cute name taken from “Twelfth Night.” (“If music is the food of love, keep it going”). Confusingly, there were also some Harry Potter themed shops.Stratford and Hogwarts, quills and wands, poems and spells. Once again, this combination may have been appropriate. Wasn't Shakespeare some sort of boy wizard magically endowed with unexplainable powers?

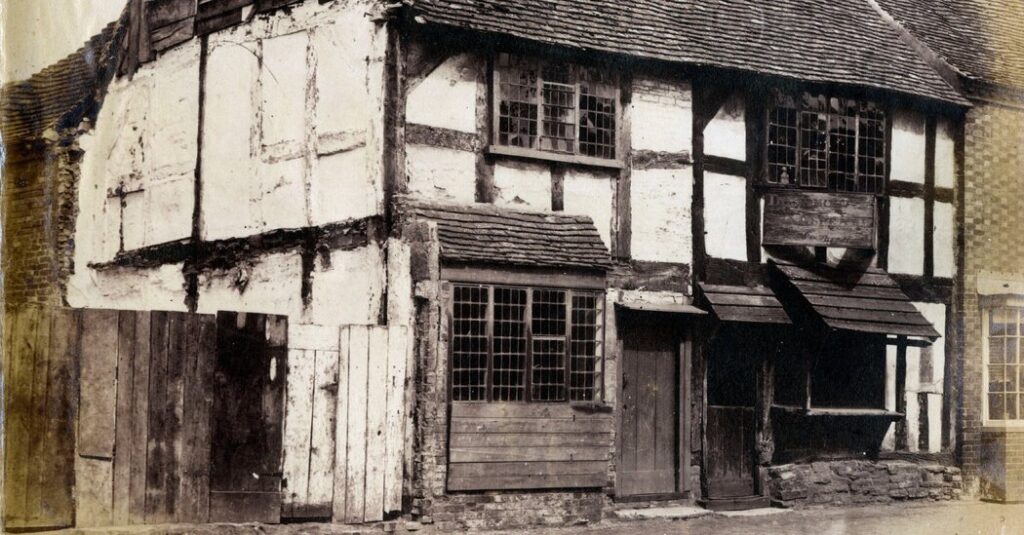

At Henry Street I arrived at my birthplace. It is an old and yellowed half-timbered house. Although it looks like a single-family house now, it was originally a row of row houses. John Shakespeare bought one tenement in this street in 1556, but also bought property in nearby Greenhill Street. It is possible that this was the birthplace of his son. He purchased the land believed to be his birthplace in 1575, 11 years after his son was born.

Birthplace believers point to records from 1552 showing that John Shakespeare was fined for leaving a pile of dung somewhere on Henry Street. Although the location has not been determined, the pile of feces has led to the theory that the boy was probably living there as a rented house at the time he was born.

Similarly, the claim that Anne Hathaway's country house is authentic is based on records showing that John Hathaway leased the 90-acre farm on which it stood around 1556, 13 years before Anne was born. . This villa may be related to the Hathaway family. However, just as there is no evidence that Shakespeare was born in a house on Henry Street, there is no evidence that Anne actually grew up there.

These traditions support Stratford's tourism industry, which was worth approximately $315 million in 2019 before the pandemic. However, they have failed to convince many skeptics over the years.

Journalist Bernard Levin wrote in the Daily Mail: “Stratford is allowing, and indeed encouraging, one of Britain's biggest fraudsters to run wild.” “I'm talking about these two monumental scams: Shakespeare's Birthplace and Anne Hathaway's Cottage.”

It didn't help that scammers figured out how to turn this story into a profit. In the early 19th century, a nativity tenant named Mrs. Hornby ran a lucrative business displaying and selling Shakespeare's “relics” to gullible visitors. The artifact was eventually exposed in an 1848 article in Bentley's Miscellany, and four different chairs, each claiming to be “Shakespeare's Chair,” had been sold over the years, and each was named after a local celebrity. It is written that it was made by a skilled craftsman.

I entered through the Shakespeare Center. The Shakespeare Center is a quirky museum that serves as a vestibule to the birthplace. None of the books Shakespeare owned or the letters he had in his possession were known to exist, so they did not exist. Instead, a glass case displayed his eight busts of Shakespeare, dating from his 1844 to his year 2000. Another case displayed Shakespeare's beer mug (1933), Shakespeare's playing cards (1974), and a Chinese-made Shakespeare action figure (2003).

Inside the birthplace, I went from room to room with other visitors. The guides entertained us with stories of Shakespeare's childhood – how he played, ate and dreamed in this room. Of course, his childhood is actually a yawning blank. There is no record of him from his baptism in 1564 until his marriage in 1582. In one room, a table was lined with books, quills, and ink, indicating an educated family, but like many illiterate people in Tudor England, he 's parents had signed the stamped document.

Other visitors murmured to each other in the museum's respectful whispers and nodded to their guides. In the late 19th century, a custodian of the birthplace named Joseph Skipsy explained that “Of the many so-called relics on display, he could not prove that any of them belonged to Shakespeare,'' and several months later the site was removed. I remembered how I resigned from my position. “There are serious questions about the place of birth itself.”

power of people's faith

Efforts to preserve the property as an official birthplace began in 1847, when it was put up for sale. In response to concerns that PT Barnum would buy the house and make it part of the show, a committee was formed to “save” the house for the public, and the group began soliciting donations. I did.

Not everyone was convinced. “The extraordinary sensations evoked by the purchase of this seedy sausage shop deserve a prominent place in the general imagination,” declared an 1848 Bentley miscellaneous article.. A reporter for another British periodical described the deception of the state, which was spending money to purchase “a mass of rubble-like lath and plaster, from which the poet was born, the very man in the moon.” He scoffed at the ease.

But the belief had already become an article of faith, and its repetition strengthened it. Publisher Charles Knight wrote at the time that the place of birth would have been a better shrine, given the complete lack of evidence, which required faith from visitors. That same year, the committee sold his birthplace at auction for £3,000 (equivalent to about $323,000 today).

The “Bad Sausage Shop” has created an unimpressive temple. So the adjacent building was demolished, walls moved, floorboards replaced, and new doorways and stairs built. The new caretakers converted it into a large and comfortable residence for a wealthy Elizabethan family, leaving the basement as “the only part remaining intact,” as scholar Sidney Lee wrote in 1901. Victorian imagination.

This committee became the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, the organization that still operates the site and maintains its authenticity. A spokesperson for the trust said: “We are aware that, as far as we currently understand, this building contains surviving parts of the building that have a traditional and close association with Shakespeare and his family. “

The trust went on to acquire more properties, including Anne Hathaway's Cottage, a thatched farmhouse where visitors could “relive Shakespeare's love story.”

Temple dedicated to baby Shakespeare

“This is the room where William Shakespeare is thought to have been born in April 1564,” says a sign in the Birth Room. Next to the bed was a cradle with a blanket and a small pillow, allowing visitors to imagine the genius baby crying next to his parents. For Victorians, the Birth Room offered the mystical possibility of contacting the poet. The visitor melodramatically recorded what he felt when he entered the room and began to cry. they fell. They kissed on the floor. Those desiring a more extended communion spent the night.

Others were not impressed. “My allusion to Stratford is not unrelated to the fact that Shakespeare was born there,'' novelist Henry James wrote after his visit. “Rather, I would like to talk about a lovely old house near the River Avon that I felt was the ideal home for a Shakespearean scholar.”

But fantasy is resilient. In the 2023 PBS documentary “Making Shakespeare: The First Folio,” Shakespeare Institute director and scholar Michael Dobson stands at his birthplace and depicts what it's like to be in “the very room in which Shakespeare was born.”

I didn't know what to do as I shuffled around the cradle with the other visitors. Should I have told the truth? Kiss it? After a reasonable stare, I moved on.

I had to pass through the gift shop to leave the store, and any remaining piety there disappeared in the wave of consumerism. Visitors were loaded up with Shakespeare T-shirts, breakfast tea and tea towels. Shakespeare's rubber duck and wind-up toys. Shakespeare Christmas ornaments, baby onesies, tote bags and fine chocolates. Faith is good business.

When I returned to Stratford last February, little had changed since my first visit. The Shakespeare Center was currently exhibiting modern artists' interpretations of the poet, including surrealist paintings of masked figures that hint at the mysteries surrounding Shakespeare. Trinket stands still sold modern versions of 18th-century mulberry wood carvings. Faith in tradition is tied to desire, the need to believe.

Where was “Immortal Shakespeare” actually born? Stories are usually more seductive than the truth.

Sealag McNeil Contributed to research.

Elizabeth Winkler is a journalist, critic, and author of Shakespeare Was a Woman and Other Heresies: How Doubting the Bard Became Literature's Greatest Taboo.

Follow New York Times Travel upon Instagram and Sign up for our weekly Travel Dispatch newsletter Get expert tips to travel smarter and inspiration for your next vacation.Are you dreaming of a future vacation? Or just an armchair trip? Check out our 52 places I want to go in 2024.