The U.S. economy continues to surprise, with May's jobs report being the latest example.

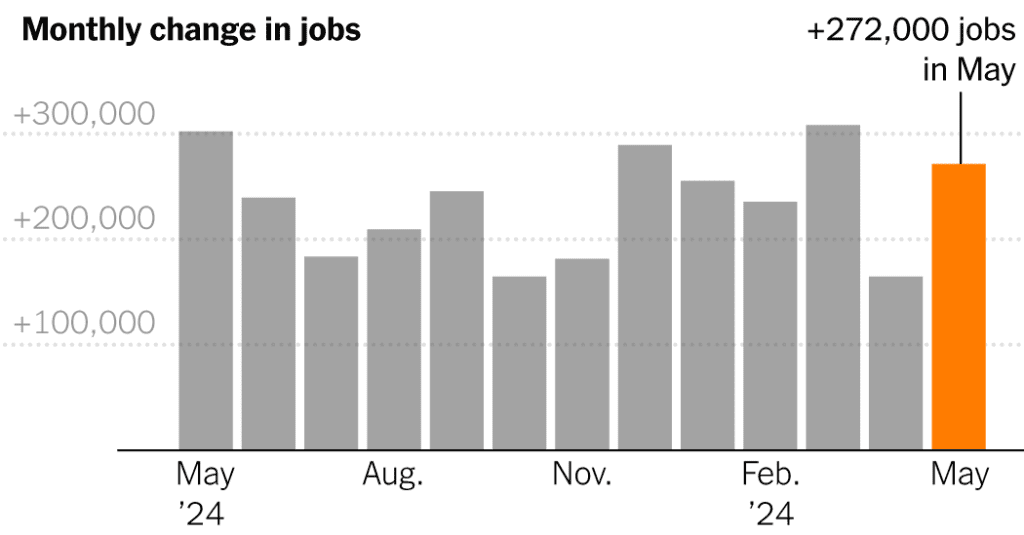

The Labor Department said Friday that employers added 272,000 jobs last month, well above what economists had expected as hiring had been gradually slowing. That's up from an average of 232,000 over the past 12 months, reversing the image that the economy is settling into a more sustainable pace.

Of most concern to the Fed, which meets next week and again in July, is that wages rose 4.1% from a year ago, suggesting inflation may not yet be overtaken.

“For those who thought a rate cut was coming in July, that door is all but closed,” said Beth Ann Bovino, chief U.S. economist at U.S. Bank. While higher wages are good for workers, sustained price increases erode their purchasing power, she noted.

Stock prices fell immediately after the report was released but then recovered and edged up slightly. Treasury yields, which reflect expectations of the Fed's interest rate movements, rose sharply and remained elevated throughout the trading day.

But the picture of the labor market acceleration is also not entirely clear. Elsewhere in the report, the unemployment rate rose to 4%, the highest since January 2022. The figure, derived from a household survey, shows no real employment growth over the past year and an increase in part-time jobs replacing full-time ones.

Data from employers generating job gains tends to be more reliable, but household surveys have been more in line with other indicators lately. Retail sales are flat. Gross domestic product fell sharply in the first quarter. Job openings are at their lowest since 2021.

As a result, most economists expect job growth to continue to slow and the unemployment rate to rise further this year.

“Outside of healthcare, we're not seeing much strength in the data,” said Parul Jain, chief investment strategist at Macrofin Analytics. “Growth is not going to be as strong in 2024. Consumers are holding back quite a bit and we expect disposable income to be impacted as well.”

Health care has been a mainstay of employment for two and a half years, accounting for 18.6% of job growth, as an aging population drives demand and the Affordable Care Act's expansion of insurance coverage makes health care more affordable for more people.

Meanwhile, the leisure and hospitality industry, which was hit harder than any other by the coronavirus lockdowns, took until April to regain employment levels seen in February 2020. Projections of a record summer travel season could lead to further job gains in the coming months, but few expect job growth to exceed last year's figures.

United Airlines, for example, said this week that it plans to add 10,000 jobs this year as the pandemic recovery shifts to organic growth, down from 16,000 in 2023 and 15,000 the year before that.

One reason job growth was stronger than expected was government hiring, which has rebounded quickly but was expected to fall as federal pandemic relief funds dry up. The sector added 43,000 jobs in May, though. A slowdown may still be ahead.

That's already clear to Peter Finch, superintendent of the West Valley School District outside Yakima, Washington. With American Rescue Plan Act funding, he was able to add mental-health counselors, tutors and other staff, but now he can't fill the positions as people quit.

“These are challenging times in education,” Dr Finch said. “With fewer resources, we can't provide the same services we've had in the past. That's the reality.”

The labor market's remarkable strength has been driven by both a recovery in legal immigration and the influx of millions of immigrants with temporary status, many of whom found jobs with the help of early work authorization. Employment for native-born workers has fallen sharply, while employment for foreign-born workers has held up, according to calculations by the WE Upjohn Institute for Employment Research.

That impact may fade once President Biden's executive order restricting asylum seekers at the southern border goes into effect.

A positive sign for the labor force is that the percentage of people ages 25 to 54 who are employed or looking for work reached 83.6 percent, the highest level since early 2002. Women are leading the way in this age group, recording their highest participation rate ever in May.

The picture is not much brighter for adults in their early 20s, whose labor force participation rate fell in May. As employers hold on to staff and fewer people leave voluntarily, there is less room for people with less work experience to get jobs, and their employment rates are falling.

Workers over 55 also have not yet returned to the workplace in large numbers — their labor force participation rate remains 2 percentage points lower than before the pandemic — but some are being forced to do so as rising costs exceed the means of retirement benefits.

John LeFoy, 67, retired from the Navy after 33 years as a mechanic. He moved to Flagstaff, Arizona, during the pandemic to be closer to his sister. With rising rent and food costs and his Subaru Outback costing more than he expected, his Social Security and civil service pensions were no longer enough to cover the costs of living. So late last year, he applied for a job at Walmart.

Working full time in the bakery and deli department (now making $20 an hour after years of wage increases) has doubled my income.

“It makes a big difference,” Lefoy said. He'll probably leave the job next year once his car is paid off, but he's enjoying the social interaction. “It's a great group of people,” he added. “It's been really beneficial for me to get back to work.”

Biden chose to focus on the job creation aspect of the report: “During my term, more than 15.6 million Americans have had the dignity and respect that comes with work,” he said in a press release. But mindful of deep concerns about persistent inflation, Biden also emphasized efforts to lower prices.

Labor market trends heading into the fall will have profound implications for the upcoming election. Most forecasters see growth slowing, but barring an external event like an escalating war or an unexpected financial crisis, a full-blown recession is the least likely it's been in years.

“We may be teetering precariously right on the edge of what we hope would be a stable equilibrium state,” said Brad Hirschbein, vice president of research at the Upjohn Institute, “where things are broadly OK, inflation continues to fall, and the labor market gets back to where we expect 150,000 to 175,000 jobs per month.”