Over a billion cups of coffee are consumed daily, including French presses, espresso and cold brewing.

University of Pennsylvania physicist Arnold Mattissen is biased towards pouring coffee, which involves manually pouring hot water over the ground beans and filtering it into a pot or mug below. Indeed, he thought that applying the principles of fluid dynamics to the process could make it even better.

Along with two students with similar minds, Dr. Mathijssen began studying methods to optimize pouring with pouring. Their science-backed advice: pour high, slow, and steady streams of water. This ensures maximum extraction from a minimum site, enhancing the flavor of your coffee without any beans or costs.

Findings published this month in the Journal Physics of Fluids highlight how the process unfolds in the kitchen stimulates new scientific directions, from making foie gras to whipping the plates of Cacio e Pepe. Second, science can enhance the art of culinary.

“Kitchen science starts with a relatively low entry barrier,” Dr. Mathijssen said. “But it's not just cute. Sometimes there's something basic about it.”

Dr. Mathijssen mainly researches the physics of biological flow, including how bacteria swim upstream within blood vessels. However, when he lost access to his lab during the Covid-19 shutdown, he literally began to play with his food. He shakes a bottle of whiskey to test the pasta's stickiness and slides the coin under the slopes made of whipped cream and honey. This interest led to physics involved in cooking meals in a 77-page review structured like a menu.

“It's completely out of control,” Dr. Mattisssen said. “I just realized that science is everywhere.”

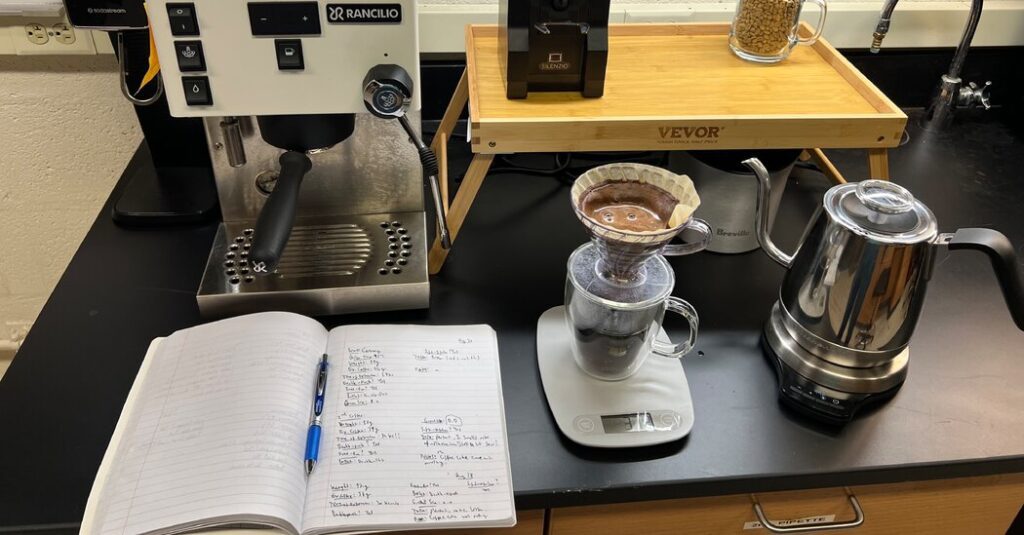

Dr. Mathijssen has since returned to the lab, but his passion for kitchen physics has been stuck. The coffee research was partly inspired by scientists in his group, and kept detailed notes on the brewing of pours prepared daily in the lab. The notes included information about where the beans came from, the extraction time and the flavor profile of the brewing.

Ernest Park, a graduate student in the lab, designed the formal experiment. Scientists used silica gel beads in glass cones to simulate the effect of pouring water into the coffee grounds from various heights, and recorded the system dynamics with a high-speed camera.