Four days after he was sworn in as Secretary of Defense, Pete Hegses directed the Academy of Military Service to scrub the ideological president's curriculum.

A few hours later, the West Point department head emailed civilians and military professors and asked for a course syllabus.

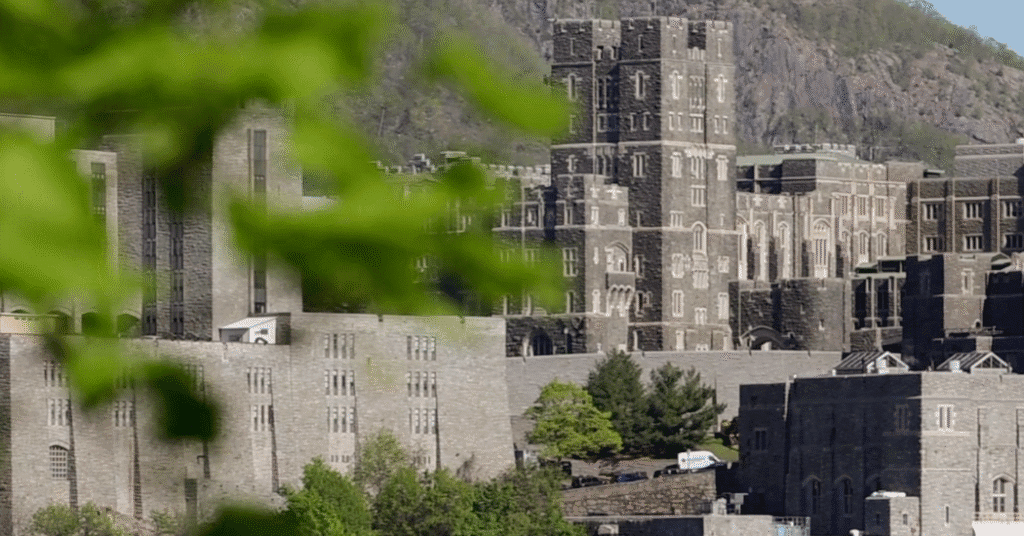

Some professors said they assumed the school would advocate for its academic programs. Instead, U.S. Military Academy leaders have launched a school-wide push to remove reads focused on race, gender, or dark moments in American history, according to interviews with more than a dozen West Point civilians and military staff. Most people were not allowed to speak to the media without academy's approval, so they spoke about the terms of anonymity.

Two classes, English and History courses, were discarded in the mid-midterm period due to breach of the new policy.

According to staff at several academies, the history professor who leads the course in Genocide was instructed to say, not to mention the atrocities committed against Native Americans. The English department wiped out the work by well-known black authors such as Toni Morrison, James Baldwin and Tanehishi Coates, officials said.

The orders of Hegseth and West Point's response issued in January have shaken up the academy, with many civilians and military professors questioning the school's commitment to academic freedom. Recently, at least two tenured professors have resigned in protest.

For a long time, academy leaders had to balance their conflicting demands. West Point is a degree-raising institution, and its commitment to academic freedom is codified both by law and by its own regulations. It is also part of the Department of Defense, whose leaders are obligated to comply with legal orders from the President and the Department of Defense.

The bitter partisan culture war has been dividing the country in recent years. He placed West Point, a military leader and instructor, in an increasingly difficult place. Mr. Hegses' orders have helped to reduce pressure.

Since taking over the Pentagon, Hegses has vowed to restore the “warrior spirit” to the power he said he had infiltrated “Marxist” professors, “Destroyer of Social Justice” and “Fekless General.”

A West Point spokesman said in a statement that the academy had reviewed the curriculum “in accordance with executive orders.” “Our strict academic program ensures that cadets develop the intellectual agility necessary to make decisions critical to the chaos of war,” the statement read.

The orders of Mr. Hegses and the changes it triggered forced West Point professors and administrators to tackle a series of difficult questions. Should they resist Mr. Hegses' orders or resign in protest? The language was confused and vague. Was there a way around that? Cadets, what was the best thing for the academy for the Army?

Some longtime academy leaders have chosen to quit.

In early March, Christopher Barth, a senior librarian at West Point, announced that he would take up another university job in 14 years. Mr. Bath's counterpart at the US Naval Academy had already been told to remove 381 books from the campus library that violated Mr. Hegses' orders. Mr. Bath was also told to identify titles that could violate the order, West Point officials said.

He told staff he was reading the American Library Association's ethics guidelines. “I have already compromised them several times,” Bath said, according to three people who attended the meeting. “I can't do it anymore.”

Philosophy Professor Graham Parsons announced in a New York Times opinion article on Thursday that the continued changes at Hegseth's order and West Point have politicized the academy and made it impossible for him to do his job.

“I am embarrassed to be associated with the academy in its present form,” he writes.

A tenured professor who had been in West Point for nearly 10 years hit her breakpoint when a university administrator told her she was no longer allowed to teach essays by novelist Alice Walker.

In an essay written in 1972, Walker explains the difficulties facing his mother (a co-craftsman and tailor in the countryside of Georgia) and encourages readers to consider the voices he lacks in American stories.

The professor asked not to name him, citing privacy concerns. She appealed to the department head and dean for the ban, but both confirmed that the texts must be cut or exchanged. In an interview, the professor said she was no longer given a clear reason for why she was no longer allowed to teach essays.

Hegseth's order prohibits professors from providing “guidance” with “critical racial theory” and “gender ideology.” The Service Academy also calls for it to teach that “America and its founding documents continue to be the most powerful force in human history.”

The professor said he knew that her resignation was unlikely to bring about change at West Point. “I can burn myself in the middle of the parade grounds and I'll forget tomorrow,” she recalls telling her boss.

However, she decided she could not continue at the academy. She explained to the officer candidates a portion of her final class in late April why she refused to find an alternative to Walker's essay, and why she left West Point.

A few days later, the cadet sent her an email saying thanked her for her courage. He wrote that it was the first time he had seen someone stand up to something that directly costs them.

West Point occupies a unique location in the Army. Within the classroom, cadets can oppose and oppose the same as private universities.

However, the academy is definitely part of the Army. Classes begin with section marchers selected by instructors, then focus on the class, take rolls, perform uniform inspections and salute. Attendance is mandatory.

According to Army regulations, West Point civilians and military professors have the freedom to “speak, express, teach and learn” in classrooms and academic fields. But they are also “servants of the nation,” as stated by Army policy, subject to the political pressure that comes with the president's orders and part of a vast federal bureaucrat.

In the interview, West Point teachers express their fear that any kind of public protest could lead to layoffs.

Some instructors have replaced prohibited texts with works that are similarly discussed by lesser known authors. Others searched for ways to register their concerns.

The West Point Philosophy course required for all second-year students at the Academy included lessons by Immanuel Kant, a key figure in Western Enlightenment Philosophy. This lesson noted that Kant was also a supporter of the racial hierarchy, encouraging cadets to tackle contradictions.

West Point administrators decided in early February that the lesson violated Mr. Hegses' orders. Instead of teaching it, a philosophy instructor dedicated the class of the day to Plato's apology. It records Socrates' defense at his trial against the mistrust and corruption of Athenian youths. According to two professors who are well-versed in the class, students discussed the importance of speaking difficult truths.

Several civilians and military professors expressed shock at the lack of debate about how Hegses' order was implemented, and how quickly it was enacted.

Two Black authors – Morrison and Coates – The work is no longer permitted to teach at West Point, but was previously welcomed as speakers on campus. In 2013, Morrison read passages from her novel about Black Korean War veterans struggling with PTSD and her return to segregated America. More than 1,500 cadets participated.

Four years later, Coates urged an audience of 800 first-year cadets to examine the myths built by the United States and even West Point after the Civil War.

“What truth do you support?” he asked them, according to a video of his speech that was recently removed from the internet. “Do you interrogate the story this country tells itself, or do you allow yourself to lie?”

Dr. Parsons, a philosophy professor who recently resigned in protest, said he spent February and March trying to figure out what he should do.

On April 10th, he accepted a year of visiting professor work at nearby Vassar College. The move meant he lost the financial security he had in tenure. It also meant leaving West Point, where he had been his professional home for 13 years.

The next day he told the supervisor he had left. He expected a difficult conversation. “I was very nervous,” he recalled.

However, his supervisor did not ask him why he was giving up his lifetime job for temporary work, he said, and he did not volunteer for an explanation.

“I think there's a lot of desire to avoid the reality of what's going on here,” Dr. Parsons said.

His experience has led him to doubt the Army and West Point leaders. “I lost faith that most people would do the right thing under pressure,” Dr. Parsons said. “That's been a really painful part of the last few months.”

But he still believed in cadets. “I believe they will succeed,” Dr. Parsons said.

Julie Tate Contributed research.