LOUISVILLE, Ky. — They called him “Nowhere.”

He was 11 years old when he showed up unannounced on the football field behind Doss High School. This was one of the few times Tim Richardson, who ran a local youth football league, didn't lean on one of his players.

“Nobody knew who he was,” Richardson said. “We didn't know what to do with him.”

The coaches were so caught off guard that they let the boy play offensively and defensively as a seventh-grader. When Richardson takes him in as an eighth-grader, he discovers that the quiet, enigmatic outsider is outpacing the rest of the team, too fast and athletic to remain in the trenches. I did. Richardson moved him to every position he could get the ball in his hands, including receiver, quarterback, and running back, making him the best player on one of the top youth teams in the country.

“I let him touch on it every other play,” Richardson said. “He might have scored 35 touchdowns that season.”

But even as he becomes a star player, with local high school coaches scouting his games, he remains an unknown boy emerging from the fog, with traces of something untold always behind him. It was approaching.

The back of his jersey even had “NO-WHERE” written on it instead of his name.

Currently, Jordan Watkins is a senior wide receiver for the Ole Miss Rebels and is ranked 16th in the College Football Playoff rankings. Last Saturday, Watkins set Ole Miss's second single-game receiving mark with 254 yards and five touchdowns in a win over Arkansas. This Saturday, the Rebels and Lane Kiffin's high-powered offense will take on the No. 3 Georgia Bulldogs in Oxford, Michigan, looking for a win that improves their chances of making the 12-team playoffs.

But before he became a record-setting starter in a top-tier SEC offense, Watkins was a kid from nowhere.

When Watkins was 8 years old, she sobbed as she watched her mother drive away in the back of a police car. I can still hear the officer saying, “Don't worry, mom will be back soon.”

He did not see her again for almost two years.

Paula Baker was a child of addiction. She started drinking at age 12, smoking marijuana as a teenager, using cocaine at 18, and became addicted to OxyContin at 21. By that time, she was a mother of two, giving birth to Jordan at the age of 17, and his younger brother Elijah a few years later.

Although she did her best to keep her drug abuse away from home and away from her children, she eventually turned to drug trafficking to feed her habit. At age 25, she was kicked out of her apartment in central Ohio, so she packed up her two sons and called a friend back home in Ashland, Kentucky, asking if they could let her stay at his house. asked. They arrived in the middle of the night, but Watkins and his brother were asleep in the back seat. Paula is arrested the next day and charged with making a deal to extort funds from her new residence, violating her parole in the process.

“That was the lowest point for me,” Paula said.

She ended up at Western Kentucky Correctional Facility, where she spent more than 18 months. The boys stayed at their aunt's house in Ashland, five hours away on the other side of the state. They had not seen each other during the entire time her mother was incarcerated. Ms. Watkins often told friends that she was on the road.

Paula was eventually paroled and given conditional release to the Healing Place recovery center in Louisville, where she was required to spend an additional 18 months. Ashland was only a few hours away, so my sister brought the boys to see us the week we arrived. They were all sitting together around the Christmas tree in the common room.

At that point, she had been sober for more than a year and a half, but she quickly realized that she had no understanding of addiction or recovery.

“I didn't know that addiction was a disease or that I wasn't a terrible person. But I heard stories of recovery and that's what I wanted,” she said. Ta. “I didn't want to live a chaotic life any longer.”

By May 2013, she had completed a recovery program, worked part-time at a healing place, and had saved enough money to secure housing with her future husband, Austin Baker. He had just completed his own recovery program. She regained full custody of her sons and moved them from Ashland to Louisville.

Watkins, 11, struggled with the transition. Watkins' father has never been a consistent figure in his life, but now he has to leave his friends in Ashland and move to a new city to live with his mother, who he has been away from for more than three years. , Austin also suddenly appeared.

“He was angry, and I understood why,” Paula said. “He didn't know what would happen if I ended up going back to prison. It was all new to him too.”

The football field was Watkins' paradise.

“When he showed up, you could see that was his outlet,” Richardson said.

Over the next few years, Watkins followed a classic recipe for rebellious behavior, lashing out at home and picking fights at school.

“It took me a very long time to forgive my mother for being gone,” Watkins said. “Looking back, I hate that because I love my mother to death, but it was obvious that I was acting it out to show how much I resented her. is.”

Richardson had heard about Watkins causing trouble, but never witnessed it on the field. Watkins sometimes asked questions about route management and planning, but mostly he kept himself quiet and hid his anger.

Things started to change when Watkins was a freshman in high school. Because he was suspended from school, he was ineligible to join the public school's football team, so Paula and Austin enrolled him in a private school, where they were barely able to cover his tuition.

“They had to sacrifice everything to allow me to play football,” Watkins said. “I was being mean and messed things up, but I could see what they were trying to do to me.”

He did not realize this right away, nor did he realize it himself. There was a lot of therapy, both as a family and as individuals. Watkins was against it at first, but then, after working with a therapist named David for several years, he became drawn to it. The two tried to eat something. Let's take a walk. Please go to the library to do your homework.

“There are still a lot of people in today's society who think therapy is for wimps and that you have to be tough as a man. I've tried to be open about the fact that therapy has changed my life. “We're working hard,” Watkins said. “David didn't expect anything in return from me and didn't require me to become someone I wasn't. He was just trying to help me.”

The wound began to heal once Watkins accepted that her mother and Austin were also trying to help.

By his senior year at Butler Traditional High School, he emerged as a three-star wide receiver and committed to play at Louisville in the 2020 class. He liked the idea of his family being a 10-minute drive from the stadium, but after two years with his hometown Cardinals, he entered the transfer portal. Watkins attracted a lot of interest, but Kiffin, who has been open about his journey to sobriety, pitched him to Ole Miss.

“Coach Kiffin told Jordan that if he wanted to go to the NFL, he needed to come play for him,” Austin said.

Watkins had 118 catches for 1,739 yards and 12 touchdowns midway through his third season with the Rebels. Paula didn't like her son moving more than six hours away, but she knows what it means for his future and he's ready for a new challenge. I recognized that. And she was ready too.

Paula has been sober for over 14 years. These days, Ms. Watkins calls herself a “mother's boy” and talks to me every day. He's also become close with Austin, being the first person Watkins called when he got a new College Football 25 video game featuring his likeness, and this summer he's been running for breath at full speed. He was the person I Facetimed right away when I hit a hole-in-one. Go green. Watkins regularly sends photos of what she makes for dinner on her flattop grill to her family's group chat.

“I've always held on to a little bit of hope. If you wake up and do it every day, things will get better,” Paula said. “And it's true.”

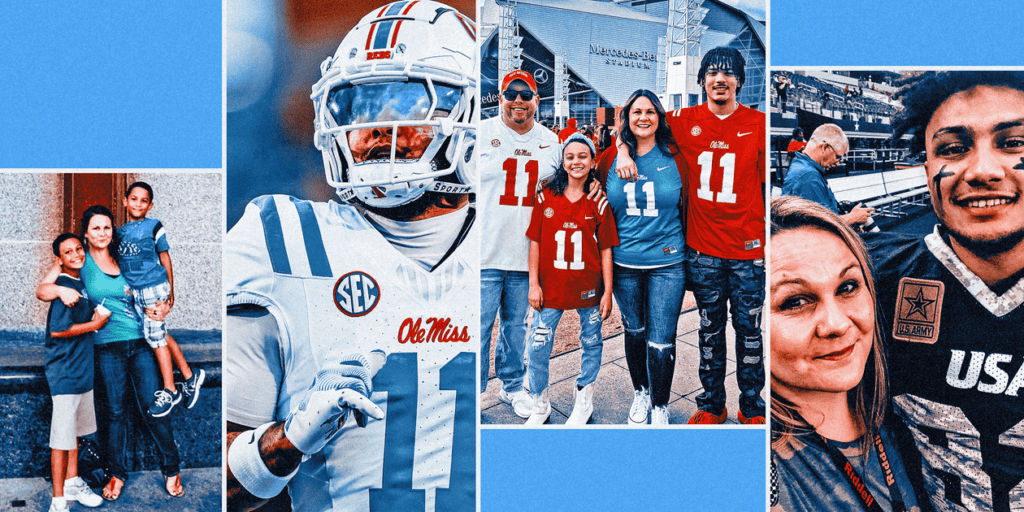

Ole Miss wide receiver Jordan Watkins, pictured with his mother Paula Baker, said therapy changed his life. (Courtesy of Paula Baker)

Ken Trogdon binge-watched the highlights of last week's Ole Miss win. The South Carolina graduate and resident is a staunch Gamecocks supporter, but he became a Rebels fan after meeting Watkins earlier this year.

“Five touchdowns? I was so excited for Jordan,” Trogdon said. “He's a very special young man.”

About 12 years ago, Trogdon, a health care administrator, founded Harbor Pass as a nonprofit organization to provide medical supplies to vulnerable populations across the United States. Its mission soon intersected with the opioid and fentanyl crisis and included efforts to distribute and inform people about naloxone (commonly known as Narcan), which can reverse opioid and fentanyl overdoses. For the past several years, Harbor Pass has worked to bring naloxone within the reach of as many people as possible.

That's what brought Trogdon to Ole Miss this winter. Harbor Pass supplied Narcan to the William McGee Center, which was established in 2019 in memory of a former Ole Miss track and field athlete who died of an accidental overdose. Anyone can stop by and receive free Narcan, no questions asked.

Trogdon approached The Globe Collective, an Ole Miss-related name, image and likeness organization, about partnering with Ole Miss athletes on social media videos to spread awareness. Watkins, a well-known football player who was comfortable being in front of the camera, was one of the athletes suggested by The Globe.

Chatting with Trogdon and Mississippi Attorney General Lynn Fitch between photo sessions, Watkins detailed his life leading up to coming to Ole Miss in 2022. He also talked about his childhood and his mother's struggle with addiction. About her time in prison and a recovery center, and how her stepfather, who was also in recovery, was revived twice by Narcan. About how his mother now works as a consultant in the recovery field for organizations like HarborPath.

Mr. Trogdon was hoping for a charismatic soccer player who would convey the message of his cause. Instead, he acquired a player with whom he “has a personal connection more than anyone else.”

Fake pills are not worth the risk.

Ole Miss wide receiver @jordantwatkins partners with HarborPath to save lives from drug overdoses and deadly fentanyl on college campuses.

🔗 https://t.co/vZE9w9Jy8j pic.twitter.com/zwN47gWSFk

— Harbor Path (@HarborpathRx) March 8, 2024

When Ole Miss' video was released in February, it racked up 100,000 views on X on its first day. Trogdon said Harbor Pass is considering expanding the campaign to additional campuses and that Watkins could become the organization's national spokesperson.

More importantly, Narcan uptake increased at the McGee Center after the video circulated, and Trogdon said the available drug was responsible for reversing the overdose on the Ole Miss campus.

It's also provided another outlet for Watkins, who also works with a recovery group in her hometown of Louisville. And his mother will provide him with input on the phone with children who may be suffering from the familiar pains of family addiction.

“It affects so many people, not just their personal use, but also the people around them,” Watkins said. “I’m really happy to be able to use my platform and experience to help.”

Recovery is not a start-to-finish process. It's a daily job and a plant that needs watering. However, after 14 years, the roots have firmly established themselves. This weekend, Paula and her family will make their annual trek of more than 400 miles to watch Watkins and the Rebels play Georgia. We support quiet children from everywhere.

“We are not perfect, but we have come a long way,” Paula said.

(Illustration: Meech Robinson / The Athletic; Photo: David Jensen/Getty Images; Courtesy of Paula Baker)