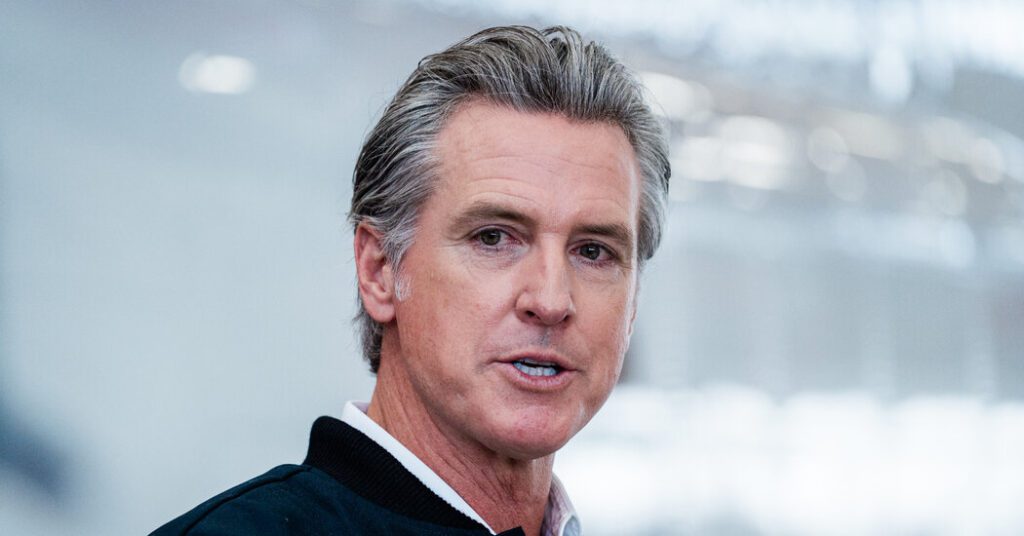

Gov. Gavin Newsom is set to escalate California's push to eradicate homeless camps on Monday, calling for hundreds of cities, towns and counties to effectively ban tent camping on sidewalks, bike paths, parks and other types of public property.

Newsom's administration raised and spent hundreds of billions of dollars on the program to bring homeless people to housing and highlight treatment. However, his move on Monday shows a more stringent approach to one of the more visible aspects of the homeless crisis. The governor has created a template for local ordinances that local governments can adopt to ban camps and clear existing ones.

California has about half the country's unsheld homeless population, a visible by-product of the temperate climate and the state's brutal housing crisis. Last year, 187,000 people in the state were homeless, according to the California Institute of Public Policy. Two thirds were not sheltered in tents, cars or outdoors.

Newsom cannot force a city to ban the model, but his publication coincides with the release of more than $3 billion in state-managed housing funds that local officials can use to install his templates. And while that's not a mission, the appeal of one of the nation's most well-known Democrats to field camps across the state suggests a shift in the party's approach to homelessness.

Once a liberal policy fight and critic of the Trump administration's voice, Newsom has stress-tested his party's position, to the point of raising ideas for Trump supporters on his podcast. Liberal approaches to camps have traditionally emphasized government-funded housing and treatment, raising eyebrows at what they call criminalising homelessness.

The Model Ordinance hopes local officials are hiring no criminal penalties by local officials, but banning homeless encampments on public property, by definition, criminalizes them. The city will decide on its own how strict the penalty should be, including arrests and quotes for those who violate the prohibition. The template's nationally issued guidance states that “we should not face criminal penalties to sleep outside when there is no other place to go.”

Frustration over the persistence of homelessness is rising within the Newsom administration and among many Californians.

California's homeless population, like its entire population, federal data released in January showed a 3% increase in the state's homeless numbers in 2024, compared to an increase of over 18% in the United States. And the number of homeless veterans and chronically homeless people has declined.

However, the camps that grew during the coronavirus pandemic as socially distancing public spaces remain a widespread problem in Southern California, Central Valley, the San Francisco Gulf Coast and Sacramento regions. And there was a clear cut between many elected officials in California and the state's federal residents.

Almost 40% of state Democrat-controlled voters said they are tired of a very creepy settlement as they are chasing the park and blocking sidewalks, according to a poll last month by the Jack Citrine Center for Public Opinion Research at the University of California, Berkeley, if they refuse shelter, they support the arrest of homeless campers. At the same time, a Democratic-led state companion survey showed that almost half of California's policy leaders and elected officials opposed the deal with law enforcement enforcement.

Previously, federal courts had found that punishing sleeping on public property was “cruel and unusual” and therefore unconstitutional. That legal situation changed last year after a Supreme Court decision empowered the government to punish people for sleeping in parks, sidewalks and other public areas.

The Newsom administration swiftly ruled in the Supreme Court, ordering state agencies to begin humanitarian removal from underpasses on state parks and highways, urging cities to do the same in their local jurisdictions.

Some work on camps with varying degrees of compassion and aggression.

Long Beach began cleaning up the camp within weeks, urging homeless people to accept shelter and treatment, but has threatened to arrest him by citing relapse residents. Fresno made sitting, lying, sleeping and sleeping in public places a misdemeanor. The San Jose City Council is weighing the proposals from Democratic mayor Matt Mahan if they reject the shelter three times.

But many California politicians are balancing. Some are worried about quoting, arresting, and prison time to further hurt homeless people. Some fear that the wrong words in local law will invite supporters to sue them.

Some say that hardlines are not necessary. Los Angeles Democratic mayor Karen Bass noted that her signature program to voluntarily move people from tent camps to motel rooms and interim shelters helped record the first double digit drop in street homelessness in the city in nearly a decade.

Still, other policymakers in Los Angeles County should be aware of both the lack of safe shelter space and the complexity of increasing new programs. They argue that the state needs to fund even more housing and care than Newsom is promoting. Until that happens, they're just arresting people, quoting, saying fuss, torture people, and moving the issues in tent camps.

Despite funding from around a tenth of the state's 500 cities and counties enact new camp restrictions, data from Washington's National Center for Homelessness Act shows that despite public pressure to address camps from San Diego to Eureka. And many municipalities are resisting the addition of shelter space.

The state funds released by the governor along with his initiative will be $3.3 billion in state management funds to expand local housing and treatment for homeless people with serious mental and behavioral health issues. The $6.4 billion state bond money was approved by voters last year.

“There are no more excuses,” Gov. Newsom said in a statement accompanied by the ordinance. “Local leaders sought resources – we provided the biggest national investment in history. They sought legal clarity – the courts delivered. Now we can provide a model where they can work quickly in humanity, settle camps and connect people to shelter, housing and care.”

Governor's city template is based on state protocols to deter homeless encampments on state lands and roads. It would explicitly make it illegal.

Also, camping on public property for three days or at night is prohibited, within 200 feet of one location. And it makes “sitting, sleeping, lying, or camping on the sidewalk in a way that obstructs a corridor, road, or bike path or pathway.”

The model ordinance requires cities to provide shelter and housing, provide at least 48 hours of notice before clearing up camps, and “any reasonable effort” to properly store moving belongings.

Management officials said California Highway Patrol, which cleans up state camps, rarely have to arrest mysterious campers. When they said, they were generally for the charge of misdemeanors such as trespassing or obstructing, delaying, or other misdemeanors of peace officers who are fulfilling their official duties. The ordinance also specifies that officers will enforce other city or state laws, including laws governing the use of controlled substances or weapons, fire laws, and public nuisance laws.

The attached state-issued guidance calls the ordinance “a potential starting point that jurisdictions may construct,” pointing to it being drawn from the approach the state has used since July 2021. That approach has surpassed over 16,000 camps and over 311,873 cubic yards of yab.