Prairie voles are stocky rodents and Olympic tunnel animals that surface in grasslands to eat grass, roots, and seeds with their chisel-like teeth, causing migraines in farmers and gardeners. is.

But for Larry Young, they were the secret to understanding romance and love.

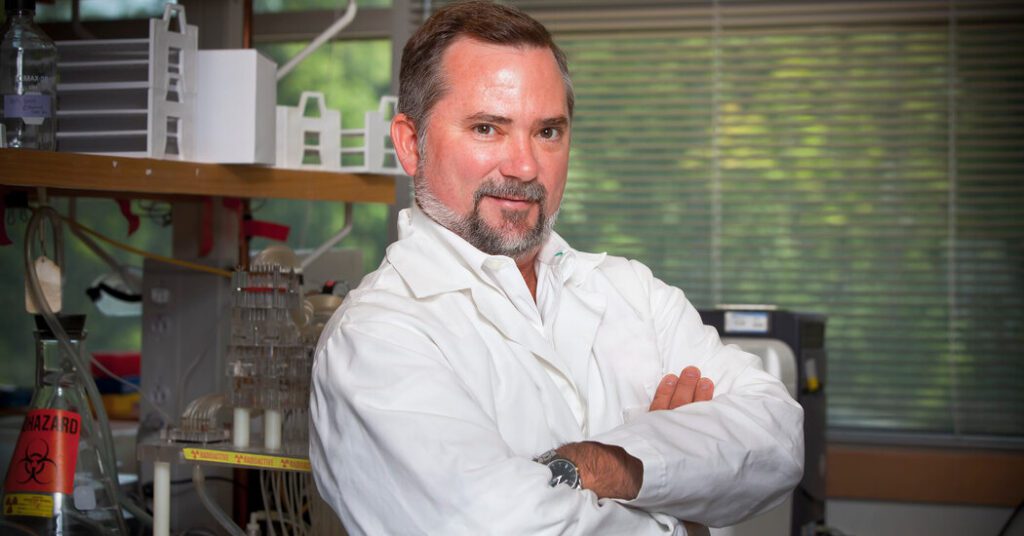

Professor Young, a neuroscientist at Emory University in Atlanta, used prairie voles in a series of experiments that revealed the chemical process of pirouetting the fluttering emotions that poets have been trying to put into words for centuries.

He died on March 21 while helping organize a scientific conference in Tsukuba, Japan. He is 56 years old. His wife, Ann Murphy, said the cause was a heart attack.

With beady eyes, thick tails, and sharp claws, prairie voles are anything but cute. However, among rodents, they have a unique domesticity. They are monogamous, with males and females forming a family unit and raising offspring together.

“Prairie voles exhibit depression-like behavior when deprived of a partner,” Professor Young told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution in 2009. “It's like being separated from your partner.”

As such, they were ideal for laboratory studies investigating the chemistry of love.

In a study published in 1999, Professor Young and his colleagues exploited a prairie vole gene involved in signaling vasopressin, a hormone that regulates social behavior. They enhanced vasopressin signaling in highly promiscuous mice.

Headline writers were amused. “Gene exchange turns lecherous rats into devoted companions,” declared the Ottawa Citizen. Fort Worth Star-Telegram: “Genetic science makes mice more romantic.” London Independent: “The gene for the 'perfect husband' has been discovered.”

Professor Young continued his research with other prairie voles, focusing on oxytocin, a hormone that stimulates birth contractions and is involved in bonding between mother and newborn.

“We knew that oxytocin was involved in mother-infant bonding, so we investigated whether oxytocin might be involved in this partner bonding,” he said in the 2019 Australian Broadcasting Corporation. said in an interview.

it was.

“If you put two prairie voles together, a male and a female, and you just give them a bit of oxytocin without making them mate, they will bond,” Professor Young said. “So this was our first series of experiments showing that oxytocin is involved in something other than maternal bonding.”

He also injected female prairie voles with a drug that blocks oxytocin, temporarily making them polygamous.

“Love doesn't really fly and disappear,” says Professor Young in The Chemistry Between Us: The Science of Love, Sex and Attraction (2012, co-authored with Brian Alexander). It is written in “The complex behaviors surrounding these emotions are triggered by several molecules in our brains. It has a very powerful influence on some of the most life-changing decisions.”

Professor Young always warned that prairie voles are not humans (of course). But just as research on mice had led to medical advances, he thought the work on prairie voles had interesting implications.

“Perhaps genetic tests will one day be available to diagnose the compatibility of potential partners. The results will accompany and even override our instincts in choosing the perfect partner. “There is a possibility that it will,” Young wrote in Nature. He added: “It may not be long before we have drugs that can manipulate our brain systems to make us love others more or less.”

In recent years, Professor Young had been researching whether increasing oxytocin under certain conditions could help autistic children who struggle with social interactions.

Larry James Young was born on June 16, 1967 in Sylvester, a rural town in southwestern Georgia. His father, James Young, and his mother, Margaret (Giddens) Young, were peanut farmers.

As a child, he had a cow named Bessie.

“It was really rural life,” Murphy said. “His dream was to work at the gas station down the street and become a manager.”

He received a Pell Grant and attended the University of Georgia with plans to become a veterinarian. One day, he dissected a fruit fly in his biochemistry class.

“That's when he became obsessed with genetics and wanted to understand the genetic basis of behavior,” Murphy said. “That became his driving force for the rest of his life.”

After graduating in 1989 with a degree in biochemistry, I completed my Ph.D. He received his PhD in Zoology from the University of Texas at Austin in 1994 and subsequently held a postdoctoral position at Emory University. He never left the university and eventually became head of the Department of Behavioral Neuroscience and Psychiatric Disorders at Emory National Primate Research Center.

Professor Young married Michelle Willingham in 1985. They later divorced. He married Murphy in his 2002 year. She is a neuroscientist at Georgia State University in Atlanta.

In addition to his wife, he is survived by three daughters from his first marriage, Lee Anna, Olivia, and Savannah Young. two stepsons, Jack and Sam Murphy; brother Terry Young; and two sisters, Marcia Young-Whitaker and Robin Hicks.

Around Emory's campus, Professor Young was also known as the Love Doctor. He was popular not only with Mr. Murphy, but also on Valentine's Day. Reporters around the world asked him to describe his love chemistry.

Someday, he said, there may be a drug that increases the urge for love.

“It's completely unethical to give this drug to other people,” he told The New York Times. ”