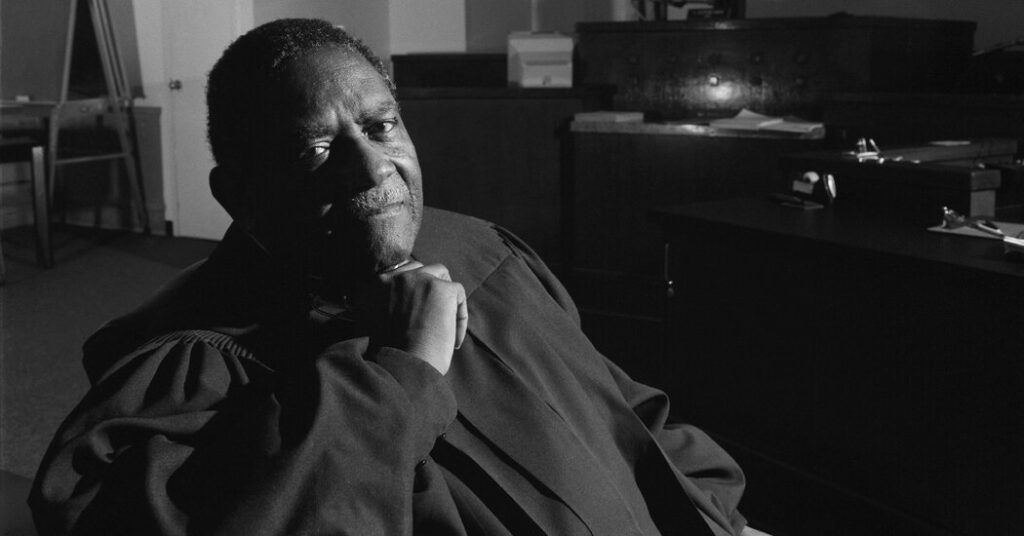

L. Clifford Davis, a civil rights lawyer who led the efforts to separate high schools in Texas, died February 15th in Fort Worth, in the face of sometimes mob violence, hostility from state politicians and threats in his life. He was 100 years old.

His daughter, Karen Davis, confirmed his death at a nursing facility.

The U.S. Supreme Court banned public school segregation in a 1954 Brown v. Topeka school board decision, but Davis worked with Thurgood Marshall in the early stages — many cities and states in the south initially rejected the sentence.

Attorneys like Davis were left to retain the local districts to explain. He started in Mansfield, Texas. The only high school in town was white. Black students had to find their own path to a black high school that travels 20 miles to Fort Worth.

On behalf of five students, Davis sued the Mansfield School District in 1955, and was upheld by the federal court of appeals a year later.

However, when black students arrived on the first day of school in September 1956, they were hugging hundreds of angry white people, some Noos. A burning cross was on display.

Davis asked U.S. Attorney General Herbert Brownell Jr. for help, but he refused. Davis later wrote to Texas Gov. Alan Sieber.

“These black students are exercising their constitutional rights,” Davis wrote. “As governor, I call on you to send additional law enforcement officers to Mansfield to ensure that law and order is maintained.”

Governor Shivers deployed the Texas Rangers, but only to maintain peace. He made it clear that he would do nothing to implement the consolidation ruling.

At one point, a friend of Mr. Davis provided him with a handgun for protection and warned him about a white vigilante. He took up the weapon but did not use it. However, he received death threats in the mail, but he shrugged them.

As tensions rose, Davis decided that the risks for students were too high, and he retreated his efforts to make them a bus to a white school.

But he kept pushing the cause. In 1959 he filed a class action lawsuit against the Fort Worth School System, which remained separate. He won, and this time agreed to a plan for the system to integrate the schools.

Such work was a microcosm of what lawyers should have tried to do, which he later reflected on.

“The philosophy that pervaded us at the time was that lawyers were social engineers,” he said in a 2014 oral history interview with the University of North Texas. “It was our job to try and use the principles of law to help bring equality and opportunity not just black people, but all.”

L. Clifford Davis (the first L. did not represent a name) was born on October 12, 1924 in Wilton, southwest Arkansas.

Wilton was deeply isolated and the local black school system was stopped in 8th grade. Clifford's parents rented a house in Little Rock, the capital of the state. There he and five of his six siblings lived when they attended high school and college.

He received his degree in business administration in 1945 and graduated from the historically black institutional Pillander Smith College (now Pillander Smith University).

Davis wanted to go to law school, but there was no Arkansas accepting black applicants, so he moved to Washington, D.C. to attend Howard University.

However, he applied for admission in 1947, as he discovered that the cost of living in Washington was too high and felt that the time was ripe for trying to separate the University of Arkansas law school.

The Fayetteville school provided him with a spot, but there is a big warning. He had to not contact white students and paid tuition in advance.

Davis declined and graduated in 1949 and stayed in Howard. But his efforts were not in vain. In 1948, Silas Hunt received the same offer and became the first black student at an Arkansas law school.

Davis initially practiced law at Pine Bluff, south of Little Rock. He moved to Texas in 1952 and settled in Fort Worth, where he became the city's first black lawyer to begin practice.

He worked with the NAACP and other civil rights groups to participate in the early stages of the suit, which became Brown v. Board of Education, led by Thurgood Marshall, the future assistant judge of the Supreme Court.

In 1983, Davis was appointed as a judge for the Criminal District Court, and the following year he won the election for the Post. He lost his re-election in 1988, but remained a visiting judge until his retirement in 2004.

Along with his daughter Karen, he was survived by another daughter, Avis Davis. His wife, Ethel (Weaver) Davis, passed away in 2015.

Judge Davis was not a person seeking the spotlight, but he eventually found him. In 2012, the Fort Worth Black Bar Association, which he discovered in 1977, was L. The name has been renamed in honor of the Clifford Davis Legal Association.

And in 2017, the University of Arkansas Law School gave him an honorary degree.

“It never crossed my mind that this was going to happen,” he told the Arkansas Democrat Gazette. “I applied 71 years ago to get my degree. Now they're going to give it to me.”