For almost a decade, Gilles Saulnier has been an energy line for the Canadian women's national team, winning two Olympic medals and a world championship.

Now she can add a new line to her resume. She threw the first real punch in the history of the professional women's hockey league in a fight with Ottawa forward Tereza Banishva.

“We were fighting there,” Saulnier said. Athletic. “She grabbed my stick and dropped it. It was like a green flag to me… I said, 'Let's go.'

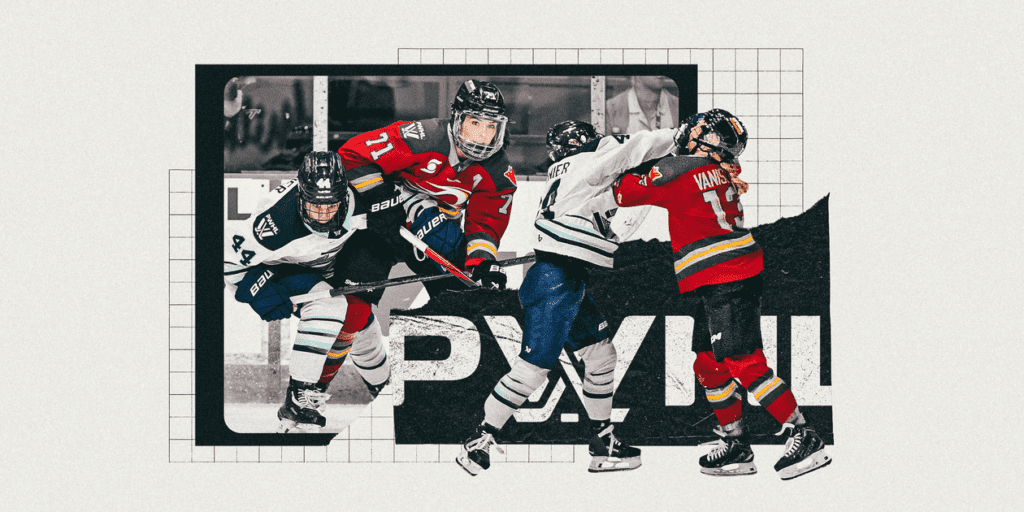

The first legitimate fight in #pwhl. 🥊 @pwhl_boston's Jill Saulnier & @pwhl_ottawa''' terezavanišovásquareoff. #pwhl@jill_saurunier @vanisovatereza pic.twitter.com/l6fr5bivmv

– Melissa Burgess (@_melissabragess) February 21, 2025

The February 20th battle during the match between the Boston Fleet and the Ottawa Charge was the first ever history in the PWHL and one of the league's most viral moments.

Fighting is nothing new to female hockey. A pre-tournament match was pre-tournament before the 2014 Olympics, and in 2016 there was another match in the now-deprecated National Women's Hockey League.

Usually there is a big hit and scrum after mouth-hitting at a professional and international level. But these moments were almost nonexistent as they fisted.

For players involved in the first battle of the PWHL, it was a natural part of the women's game and the product of the improved physicality allowed in the league.

It's deeper

The Art of Hitting in Female Hockey: How do PWHL players adapt to the more physical games?

“It's a fierce game, a physical game, and we're all very competitive,” said Saulnier, a Boston advance, after a January deal from New York Sirens. “That's how the chip fell into the corner.”

The build-up to the fight included a hit by Saulnier against one of Ottawa's top scorers, Banishova and at least two extra cross-checks. When Banishva rose to her feet, she threw a Saurnier stick to the ground.

“The next guaranteed move felt tough,” Saulnier said. “At this point, it was physical and that fight had to happen. It was right there and it was a message from both sides.”

Neither player dropped gloves, as is conventional in men's hockey. The female player wears a full cage to protect her face. In both leagues, players are not allowed to remove helmets to fight.

“It just looks ridiculous to completely remove the gloves,” Saulnier said.

Nearly 6,000 fans from Ottawa's TD Place Arena were standing up. The same was true for players on each bench. Five minutes after the fight, Ottawa defender Ronja Savolainen scored to play the game 2-1 in the second half of the third season. When Vanišová got out of the penalty box, she only scored three seconds left in the game and sent it into overtime, registering the first unofficial “Gordie Howe Hat Trick” in league history.

“I thought it was amazing, it moved the fans,” Saulnier said. “I'm sure I'll get some boos next time I go there, but it was all respectful and fun.”

Ottawa ultimately lost 3-2 in overtime, with Saulnier and Banishava sharing a “good fight” moment at the handshake line after the match.

“You see the strength of the game, and that's the fun part of this league,” Ottawa coach Carla McLeod said after the game. “Neither player has retreated and I think there's a bit of talk about that. This isn't bad for the game either.”

The fight made global news with TMZ headlines and the Daily Mail, outlets that don't cover women's hockey. And, although it went viral on social media, 16 million people across North America saw Canada and the US in the face-off finale of four countries.

Last week, fans handed me a Saulnier bracelet that spells out Beads' “Fight Club” and “Jilsaurunier Fight Club.”

“I think more people reached out than when we won the gold medal,” said Saulnier, a member of the 2022 Canadian Olympic Team. “Obviously you shouldn't compete with every game, but I actually think it was good because I looked more at the league.”

The PWHL, officially launched in January 2024, will be exposed. The fight was also good proof that the league was full of skilled players who could not only play finesse and speed, but also embrace physicality. Still, fights aren't what they want to be the norm.

The league's rules book clearly states that “combat is not part of the PWHL game.” And before last month's argument, there was little clearer about the penalties that a judge could impose, other than the fact that the judge was punished and kicked out of the game.

Saulnier and Vanišová were given only rough minors for their fight, which caused confusion over the rules. Last week, the league revealed that the fight will be punished for a five-minute major penalty and game cheating.

According to Saulnier, Boston's general manager Danielle Marmer calls it “The Gilles Saulnier Rules.”

The new rules should prevent players from fighting frequently. In a short 30-match season, players may be willing to add additional games just to boost postwar energy. Also, equipment barriers remain a natural deterrent for fighting women's hockey.

Beyond that, combat is not common at other levels of women's games. These skills are not usually taught because youth girls hockey don't even allow body checks. In Boys Hockey, body checks were introduced at under-14 levels, and by the time players reached professional levels, combat was part of the game.

Saulnier doesn't think her fight will open the floodgates at more such moments in the future. But she said it was certainly not the last time she would see a fight in professional women hockey.

“On a physical level, you don't see it in PWHL,” she said.

(Illustrated by Demetrius Robinson / Athletic;Photo: Troy Parla / Getty Images)