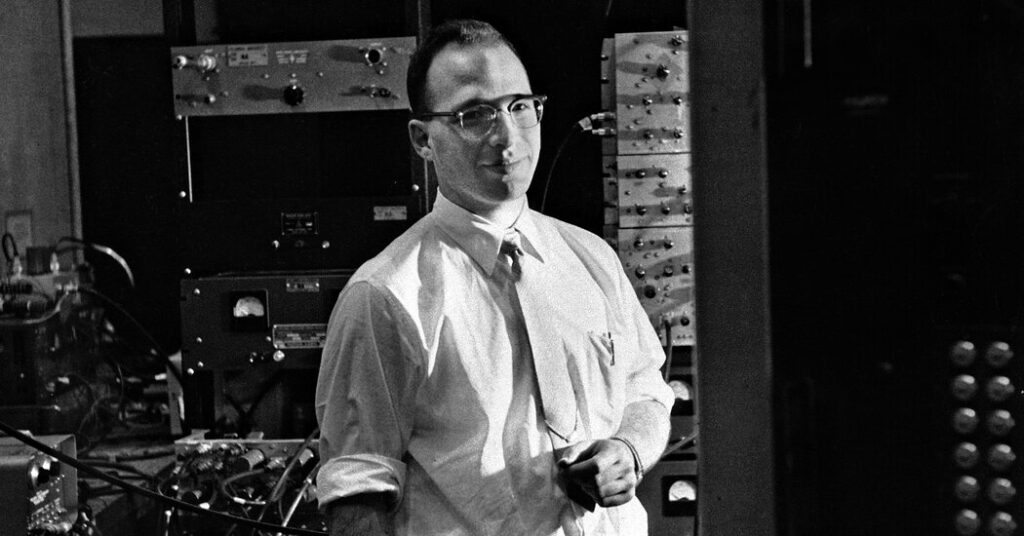

American hydrogen bomb architect Richard L. Gerwin, who shaped the postwar government's defense policy, laid the foundation for space structure and amazing medical and computer insights, died Tuesday at his home in Scarsdale, New York.

His death was confirmed by his son Thomas.

Dr. Gerwin, a multi-associate physicist and geopolitician, was only 23 years old when he built the world's first fusion bomb. He later became a scientific adviser to many presidents, designing the Pentagon weapons and satellite reconnaissance system, advocating the balance of Soviet-Americans in nuclear terrorism as the best way to survive the Cold War, and endorsing a verifiable nuclear weapons control agreement.

His mentor, Nobel Prize winner Enrico Fermi, called him “the only true genius I've ever met,” but Dr. Gerwin was not the father of the hydrogen bomb. Hungarian-born physicist Edward Terrer and Polish mathematician Stanislo Ullam, who developed the theory of bombs, may have a greater claim to the sobriquet.

However, from 1951 to 52, Dr. Gerwin was then an instructor at the University of Chicago and a summer consultant at the Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico and was designed. A real bomb using Teller-Ulam's idea. The experimental device, named Ivy Mike, named Cord, was shipped to the Western Pacific Ocean and tested on atolls in the Marshall Islands.

The device was not like a bomb just to prove the concept of fusion. It weighed 82 tons, and was not inhabited by plane and looked like a giant thermos. Soviet scientists who did not test comparable devices until 1955 called it intermittently the installation of thermonuclear nuclei.

But at the enewetak atoll on November 1, 1952, it said: the imaginative fusion of atoms blows a flash of instant flashes of blind light, and a fireball that is two miles wide to distant observers, with a force of 700 times greater than the atomic bomb that destroyed Hiroshima, which destroyed Hiroshima for 100 miles in 1945.

As secrets masked the development of the American thermonuclear weapons program, Dr. Gerwin's role in creating the first hydrogen bomb was virtually unknown for decades outside the government's defense and the small circle of intelligence reporting agencies. His name was Dr. Terror, who had long been associated with the bomb, and first praised him publicly.

“According to Gerwin's design, this shot was fired almost exactly,” Dr. Teller said in a 1981 statement that he recognized the important role of the young genius. Yet, that late recognition was barely notified, and Dr. Gerwin was not publicly known.

Compared to later thermonuclear weapons, Dr. Gerwin's bomb was crude. Nevertheless, its raw power reflects the sacred Hindu texts of the Bagavangita, recalling the first film of the atomic bomb test in New Mexico in 1945 and the appalling reaction of its creator, J. Robert Oppenheimer.

For Dr. Gerwin, that was a little.

“I didn't feel that building a hydrogen bomb was the most important thing in the world, or even my life at the time,” he told Esquare in 1984. I asked about my feelings of guilt. “I think it would be a better world if there were no hydrogen bombs.

Pivoting to IBM

The first hydrogen bomb was built to his specifications, but Dr. Gerwin was absent to witness the explosion at Enewetak. “I've never seen a nuclear explosion,” he said in an interview in the 2018 obituary. “I didn't want to spend the time.”

Dr. Gerwin said he was at a crossroads in 1952 after a successful hydrogen bomb project. He was able to return to the University of Chicago. He received his PhD under Fermi, and is now an assistant professor, and has promised a life at one of the most prestigious academic institutions in the country.

Or he was able to embrace a much more flexible job at International Business Machines Corporation. He provided the appointment and use of faculty members at the Thomas J. Watson Institute at Columbia University, making his research interests widely free. He also managed to continue working as a government consultant in Los Alamos and Washington.

He chose to trade IBM and lasted for 40 years before retiring.

For IBM, Dr. Gerwin tackled an endless stream of purely applied research projects that bring in astounding patents, scientific papers and technological advances in computers, communications, and medicine. His research was important in the development of magnetic resonance imaging, high-speed laser printers, and subsequent touchscreen monitors.

A dedicated Maverick, Dr. Gerwin worked hard for decades to advance gravitational wave hunting. Ripples on the fabric of space-time predicted by Einstein. In 2015, the expensive detector he supported successfully observed ripples and opened new windows into space.

Meanwhile, Dr. Gerwin continued to work for the government and consulted about national defense issues. As an expert on weapons of mass destruction, he helped select Soviet targets and led research into land, marine and aviation warfare, including nuclear armed submarines, military and civilian aircraft, satellite reconnaissance and communications systems. Many of his works remained secrets, and he was barely known to the public.

He became advisers to presidents such as Dwight D. Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson, Richard M. Nixon, Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton. He has also become known as the voice of President Ronald Reagan's proposal for a space-based missile system commonly known as Star Wars to protect the nation from nuclear attacks. It was never built.

One of Dr. Gerwin's famous battles had nothing to do with national defense. In 1970, as a member of Nixon's Scientific Advisory Committee, he violated the president's support for the development of supersonic transport aircraft. He concluded that SST was expensive, noisy and bad for the environment and commercial dad. Congress has withdrawn the funds. The UK and France have subsidized the development of their own SST, Concorde, but Dr. Garwin's predictions proved largely correct, and interest has waned.

Clash with the army

A little professor man with more hinting flyaway hair than the Congress hot sheet and gentle voice suitable for university lectures, Dr. Gerwin became an almost legendary figure in the defense facility, writing speeches, writing and writing articles, and testifying before lawmakers about what he called the Pentagon's false choice.

Some of his feuds with the army were bitter and long-term. They included the battle over the B-1 bombers, Trident nuclear submarines, the MX missile system and the MX missile system, a network of mobile-based intercontinental ballistic missiles, one of the deadliest weapons in history. Everything eventually joined America's vast Arsenal.

Dr. Gerwin was frustrated by such a setback, but he moved forward. His core message was that America should maintain a strategic balance between the Soviet Union and nuclear power. He opposed weapons and policies that threatened to disrupt that balance. He liked that Moscow was more interested in living Russians than in dead Americans.

Dr. Gerwin supports the reduction of nuclear weapons, including the 1979 Strategic Arms Restrictions Treaty (SALT II), negotiated by President Carter and Soviet Prime Minister Leonid Brezhnev. However, Dr. Gerwin argued that mutually guaranteed destruction was the key to maintaining peace.

In 2021, he joined 700 scientists and engineers, including 21 Nobel Prize winners, and signed an appeal asking President Joseph R. Biden Jr. to pledge that the United States would never use nuclear weapons first in conflict. Their letter also called for an end to the American practice of giving the president the sole authority to order the use of nuclear weapons. They said the curb on that authority would be “an important safeguard against future presidents who could order voluntary or reckless attacks.”

The idea was politically sensitive and Biden did not make such a pledge.

Dr. Gerwin told Quest Magazine in 1981: “Nuclear weapons are good, and what's good up to this point is massive destruction, and the threat prevents nuclear attacks.

5 o'clock with the child

Richard Lawrence Gerwin was born in Cleveland on April 19, 1928 and is older of two sons, Robert and Leona (Schwartz) Gerwin. His father was a technical high school electronics teacher during the day and a cinema projectionist at night. His mother was the Attorney General. At a young age, Richard, known as Dick, showed incredible intelligence and technical capabilities. By 5 he had repaired his family's appliances.

He and his brother Edward attended Cleveland public schools. Dick graduated from Cleveland Heights High School in 1944 at the age of 16 and in 1947 he received his Bachelor of Arts in Physics from the present Case Western Reserve University.

In 1947 he married Lois Levy. She passed away in 2018. In addition to his son Thomas, he was survived by another son Jeffrey. My daughter, Laura. Five grandchildren. and one great grandson.

Under Fermi's guidance at the University of Chicago, Dr. Gerwin received his master's degree in 1948 and a doctorate in 1949, earning the highest mark in the doctoral exams the university has ever recorded. He then joined the faculty, but Fermi urged him. He spent his summer at Los Alamos Lab, where his H-bomb unfolded.

After resigning in 1993, Dr. Gerwin served as chairman of the State Department's Arms Management and Non-Proliferation Advisory Committee until 2001. He served on the committee in 1998 to assess the ballistic missile threat to the United States.

Dr. Gerwin's home in Scarsdale is not far from the long-standing base at IBM Watson Lab, which moved from Columbia University to Yorktown Heights in Westchester County in 1970.

He made faculty appointments at Harvard University, Cornell, and Columbia. He has obtained 47 patents, wrote 500 scientific research papers, and wrote many books, including Nuclear Weapons and World Politics (1977 with David C. Gonpert and Michael Mandelbaum), and Megawatts and Megatons: The Turning Points of the Nuclear Age. (2001 with Georges Charpak).

He was the subject of the biographies. “The True Genius: The Life and Work of Richard Gerwin, the Most Influential Scientist You've never heard of” (2017), Joel N. Sherkin.

Many of his honors included the 2002 National Medal of Science, the National Medal of Science, the highest national award for science and engineering achievements given by President George W. Bush, and the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation's highest civilian award given to President Barack Obama in 2016.

“He was messing around with his father's film projector and never met any issues he didn't want to solve,” Obama said in a light introduction at the White House. “Reconnaissance satellites, MRI, GPS technology, touchscreens – everything supports fingerprints. He even patented a shell washing machine.

William J. Broad and Ash Wu contributed the report.