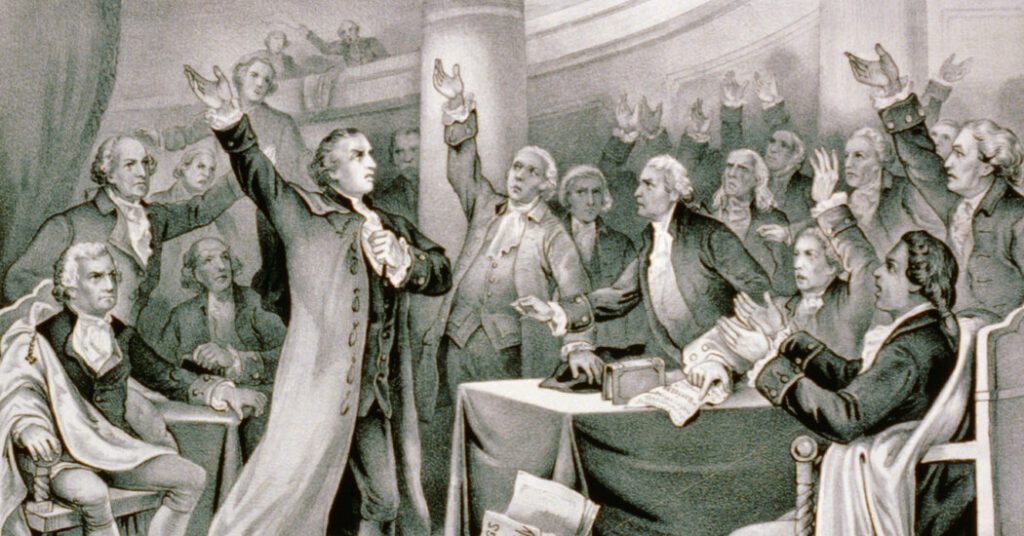

Revolutionary hero Patrick Henry knew this day would come. He may not have anticipated details like the presence of a porn star in his hotel room or the illegal bribe he took to silence her. But he feared that a criminal would soon assume the presidency and use his power to thwart those who would hold him accountable. “Get rid of a President; make a King,” he proclaimed.

That's exactly what the Founding Fathers wanted to do to escape the control of an all-powerful monarch. But as hard as they tried to institute checks and balances, the system they built to hold errant presidents accountable ultimately proved to be shaky.

Whatever rules Americans thought were established are now being rewritten by Donald J. Trump. Trump, a former president and potential future president, has already shattered many barriers and precedents. The idea that 34 felony counts do not automatically disqualify a person, and that a convicted felon could be a viable candidate for commander in chief, upends two and a half centuries of assumptions about American democracy.

And a return to the presidency would raise fundamental questions about the limits of Trump's power in a second term. If he wins, he will have overcome two impeachments, four criminal indictments, civil judgments for sexual abuse and business fraud, and a felony conviction, making it hard to imagine what institutional deterrents could prevent him from misusing or overreaching.

Moreover, the judiciary may not be able to act as a check on the executive branch as it has in the past. If no other cases are heard before the election, it could take another four years before the courts can consider whether the newly elected president endangered national security or attempted to illegally overturn the results of the 2020 election (as he has been charged). As things stand, the Supreme Court may grant Trump at least some immunity, even before the election.

Analysts say that while Trump must still operate within our constitutional system, he has already demonstrated a willingness to push its boundaries. While president, he argued that the Constitution gave him the right to “do whatever I want.” After leaving office, he called for “repealing” the Constitution so he could quickly return to power without re-election, and vowed to dedicate a second term to “retribution.”

Trump's advisers are already drawing up ambitious plans to strengthen his power in a second term by purging the civil service and making more political appointments. Trump has threatened to prosecute not only President Biden but also anyone he sees as an enemy. In asking the Supreme Court for immunity, Trump's lawyers argued that in some cases a president can order the assassination of a political opponent without facing criminal penalties.

“There's just no historical precedent to help us,” said Jeffrey A. Engel, director of the Center for Presidential History at Southern Methodist University. “What's interesting is not that a former president was tried and convicted, as the Founding Fathers would have expected, but that he remains a viable candidate for the presidency, something that would have surprised and ultimately disappointed the Founding Fathers.”

The problem of how to create empowered executive power without making the president an unaccountable monarch preoccupied the Framers when they wrote the Constitution. They divided powers into three branches of government and saw impeachment as a way to check an out-of-control president. They even made it clear that an impeached president could be prosecuted for crimes even after he was removed from office.

But even then, there were those who worried that restrictions alone would not be enough, including the patriot Henry, famous for his “Liberty or Death” speech, who warned at the Virginia Constitution ratification convention in 1788 about the possibility of “absolute tyranny.”

“His argument is that if such a criminal president were to come to power, he would find that there was little that could be done to stop him,” said Brown University professor Corey L. Brettschneider, who writes about Henry in his upcoming book, “The President and the People: Five Leaders Who Threatened Democracy and the Citizens Who Fought to Defend It.” “He goes so far as to argue that such a president would claim the throne.”

“My contention is that this warning is even more true now, given the immunity a sitting president can enjoy from prosecution and the impotence we have seen after two impeachment attempts,” Brettschneider added.

In his new book, “Treason: How Illiberalism Will Divide America Again,” Robert Kagan, a scholar at the Brookings Institution in Washington, warned that a second term for Trump could lead to unbridled abuse of power.

“Given the enormous powers wielded by the President of the United States, and his ability to control and direct the Department of Justice, the FBI, the IRS, the intelligence agencies and the military, what is to prevent him from using the power of the state to go after his political opponents?” Kagan wrote.

To some of Trump's supporters and even critics, these concerns are overdone. They say Trump is joking or trying to rile up his critics when he makes provocative statements about being a “dictator for a day.” They say the real danger is not a lack of presidential accountability but the politicization of the justice system against Trump.

George Washington University law professor Jonathan Turley, who was in the Manhattan courtroom on Thursday when the jury returned its guilty verdict, called the case against Trump a “blatant politicization of the criminal justice system” and a “thrill murder” by his opponents. “What happened in that room has a cost,” he told Fox News. “It has a cost to the rule of law.”

Even those who don't support Trump say warnings about unchecked government are overblown. Eric Posner, a professor at the University of Chicago Law School who wrote a book calling Trump a demagogue testing American democracy, said the former president was “too weak” and incompetent to run a true dictatorship.

“Trump was and is many things, most of them bad,” Posner wrote in response to Kagan's Washington Post column last winter. “But he was no fascist as president, and he won't be a dictator if reelected.” Trump incited mobs and spread lies to stay in power, Posner added, but “has completely failed.”

U.S. lawmakers have struggled to devise an independent mechanism for enforcing presidential accountability, but have found it too politically tainted to lose public trust. The issue has been raised repeatedly over the past half century, but no consensus solution has emerged.

Nine of the last 10 presidents have had special or independent counsel investigate themselves or someone in their administration, with the only exception being Barack Obama (Gerald R. Ford's campaign finances were investigated while he was vice president, but no indictments were filed).

Neither of the two men who faced serious risk of criminal prosecution before Trump went that far: Richard M. Nixon avoided prosecution for covering up the Watergate scandal but resigned and was later pardoned by his successor, Ford, and Bill Clinton avoided possible perjury and obstruction of justice charges arising from his affair with Monica S. Lewinsky by making a deal with prosecutors in his final days in office, pleading guilty to lying under oath and renounced his license to practice law.

After President Nixon fired the first special prosecutor investigating Watergate, Congress passed the Independent Counsel Act, which would have theoretically created a prosecutor insulated from politics, but Republicans became disillusioned with that model after Lawrence Walsh's Iran-Contra investigation, and Democrats became disillusioned after Ken Starr's Whitewater investigation, so Congress allowed the act to lapse.

The special counsels who investigated former presidents, including Trump and Biden, were appointed by the attorney general at the time. Although they have significant powers, they are not fully independent, which means their investigations and conclusions are often criticized as politicized, even in the absence of evidence of interference.

Having endured Special Counsel Robert S. Mueller's Russia investigation and Special Counsel Jack Smith's current election interference and classified documents investigation, Trump is unlikely to appoint an attorney general who would allow Smith's investigation to continue, much less appoint a new special counsel to investigate him.

Instead, Trump has proven that relentlessly forging ahead despite scandals, investigations and trials has paid off politically — at least so far. He is on track to win the Republican nomination for a third time and has at least a strong chance of beating Biden to return to the White House, which would set a new standard for who is fit to be president.

“My biggest takeaway is how fortunate we are as a nation that presidents have, for the most part, behaved with dignity and at least respected the dignity of the office,” said Lindsay M. Cherbinski, the incoming director of the George Washington Presidential Library and author of “The Making of a President,” a book about John Adams due for publication in September. “This guilty verdict underscores how vehemently Trump has rejected that tradition.”