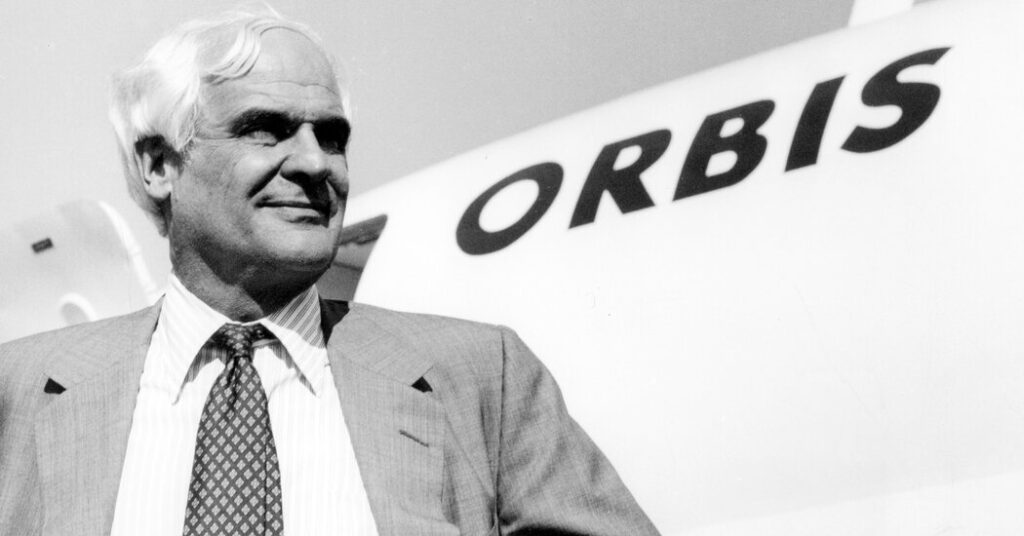

David Patong, an ideal and innovative ophthalmologist who started Project Orvis, converted United Airlines jets into flight hospitals, took surgeons to developing countries, educated local doctors, and died on April 3 at his home in Reno, Nevada.

His death was confirmed by his son Townlee.

Dr. Patong (pronounced Pay-Ton), the son of a prominent New York ophthalmologist, including Iranian Shah and investor J. Pierpont Morgan horse, taught at the Wilmer Eye Institute at Johns Hopkins University in the early 1970s when he was disappointed by his disappointment by increasing cases of preventable blindness in remote areas.

“We needed more ophthalmologists,” he wrote in his memoir in “Second Sight: A View from Tye An ay Doctor's Odyssey” (2011). “However, there is a need to strengthen medical education for existing physicians.”

But what do you think?

He considered shipping trunks of equipment in almost the circus method, but it presented logistical challenges. He contemplated the possibility of using medical vessels like Project Hope, a humanitarian group sent all over the world. It was too late for him.

“I believe that the big is beginning to become a reality shortly after the first moon landing in 1969,” writes Dr. Patong.

And the idea of Moonshot hit him: “Are the aircraft the answer? We can convert a plane that is large enough to an operating room, an educational classroom, or any facility we need.”

All he needed was an airplane. He asked the military to donate it, but it wasn't a starter. He approached several universities to buy money, but the administrator refused him.

“David was willing to take risks that others wouldn't,” Bruce Spivey, founder of the American Academy of Ophthalmology, said in an interview. “He was charming. He was inspiring. And he didn't quit.”

Dr. Patong decided to raise the funds himself. In 1973 he founded Project Orvis with wealthy and connected societies groups such as Texas oilmen Leonard F. McCollum and Betsy Trippe Wainwright.

In 1980, Trippe convinced United Airlines CEO Edward Carlson to donate his DC-8 Jet. The US International Development Agency has donated $2.25 million to convert the plane into a hospital with operating rooms, recovery areas and classrooms with televisions, allowing local health workers to watch the surgery.

The surgeon and nurse agreed to spend 2-4 weeks abroad and volunteered for service. The first flight in 1982 was to Panama. After that, the plane went to Peru, Jordan, Nepal and other places. Mother Teresa once visited. So did Cuban leader Fidel Castro.

In 1999, the Sunday Times of London magazine sent reporters to Cuba and wrote about the plane, now known as the Flying Eye Hospital. One of the patients who arrived was a 14-year-old girl named Julia.

“In developed countries, Julia's condition is nothing more than an inspiration,” the Sunday Times article states. “It's almost certain she's got uveitis, an inflammation in her eyes. This can be cleaned with drops. In the UK, even cats are easily treated.”

Her doctor was Edward Holland, a well-known ophthalmologist.

“The Netherlands use small knifes to create openings so that the instrument can be put into the eye, and quickly pulls Julia's scar tissue,” the Sunday Times article states. “As the tissue is pulled apart, the dark, liquid pupils of invisible for ten years are revealed. It's an intimate and moving moment. This is the chamber music of medicine. He then breaks down and removes the cataract and implants the lens so that the eyes retain their shape.”

The Cuban ophthalmologist watching in the viewing room applauded.

However, after the surgery, Julia was still unable to see.

“And then a little miracle begins,” the article said. “As the swelling starts to subside, she discovers about the world around her. Every few minutes you can see something new.”

David Patton was born in Baltimore on August 16, 1930 and grew up in Manhattan. His father, Richard Townlee Patong, specialising in corneal transplants, founded glasses for visual recovery. His mother, Helen (Meserve) Paton, was an interior designer.

In his memoirs, he stated that he “bred in the institution's wonderful, intelligently keen, widely travelled people.” His father practiced on Park Avenue. His mother threw a party at her home on the Upper East Side.

David attended Hill School, a boarding school in Pottstown, Pennsylvania. There he met James A. Baker III, the Texans. They were roommates and lifelong friends at Princeton University.

“David came from a very privileged background, but he was a very likable guy who was on earth,” Baker said in an interview. “He had a straightforward purpose in life. He was a student hell that was far better than me.”

After graduating from Princeton in 1952, David received a medical degree from Johns Hopkins University. He worked in senior positions at the Wilmer I Institute and served as chairman of the ophthalmology department at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston.

In 1979, while trying to procure Project Orvis' planes, he became medical director of King Khaled Ice Specialist Hospital in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

“In my duty, he wrote in his memoirs: “I provided eye care to many of the princes and princesses of the kingdom, about 5,000 people each said.

Dr. Paton's marriage to Jane Sterling Treman and Jane Franke ended with divorce. He married Diane Johnston in 1985. She passed away in 2022.

In addition to his son, he was survived by two granddaughters.

Dr. Patong resigned from his role as Medical Director of Project Orvis in 1987 after a dispute with the board of directors. That year, President Ronald Reagan awarded him the Presidential Citizen Medal.

Although official connections with the organization were over, he occasionally served as an informal advisor.

The organization now known as Orbis International is on the third plane, an MD-10 donated by Federal Express.

From 2014 to 2023, Orbis performed over 621,000 surgeries and procedures, providing over 424,000 training sessions to doctors, nurses and other providers, according to its latest annual report.

“Airplanes are exactly such a unique venue,” said Dr. Hunter Shelweck, the organization's vice president of clinical services and technology, in an interview. “It was an incredibly bold and visionary idea.”