Bologna's Garisenda Tower has exhibited an alarming tilt and endured insults and trauma over the centuries. Dickens said it was “unsightly enough” even though it was an anomaly, and Goethe said it was a “disgusting sight”. Then there were earthquakes, Allied bombing of the city during World War II, and urbanization that doomed other towers to destruction.

Through it all, Garisenda is a beloved symbol of this medieval city, a reminder of the past when important families and communities remembered their status and built towers for defense.

But now Garisenda is in trouble.

Last year, alarmed experts issued what they called an “engineering code red” after sensors attached to the monument, which is tilted at an angle of 3.6 degrees, detected “unusual movement.”

Garisenda was sealed off in October, a bright red protective wall was installed along part of its perimeter to minimize damage if the tower were to topple over, and a group of experts looked ahead to the future while being mindful of the dangers. They decided to work on a plan to protect the tower. A sign of impending trouble.

“This is like a patient in an intensive care unit, whose vital signs continue to be monitored,” said Gilberto Daravalle, a structural engineer who has been in charge of interventions to stabilize the 157-foot tower since 1997. There are 64 pieces of equipment that we monitor on a regular basis.”

He and other experts called to protect the tower are now looking to another famous Leaning Tower for answers and proposing solutions. Bologna Mayor Matteo Lepore announced last week that the city would adopt a temporary system of pylons and cables, which has been used successfully in Pisa, home to the most famous Leaning Tower.

The idea is to attach two pylons to special structures on the tower with cables that are expected to exert a reaction force if the tower begins to tilt more dangerously.

Once the garisenda is stable enough for workers to work safely, work can begin on reinforcing the tower, especially the foundation, by injecting a mixture of selenite and compatible mortar into the base cavity. The final stage will involve repairing the top of the tower so that it remains stable for many years to come.

“We have to stabilize the situation as quickly as possible to avoid things getting worse,” Lepore said of the early stages of work, so more considered decisions can be made.

Bologna may be best known for its rich food (one of its nicknames is “La Grassa”, or fat food). Italy's oldest university (another nickname is “La Dotta”, the learned one). It was added to the UNESCO World Heritage List three years ago.

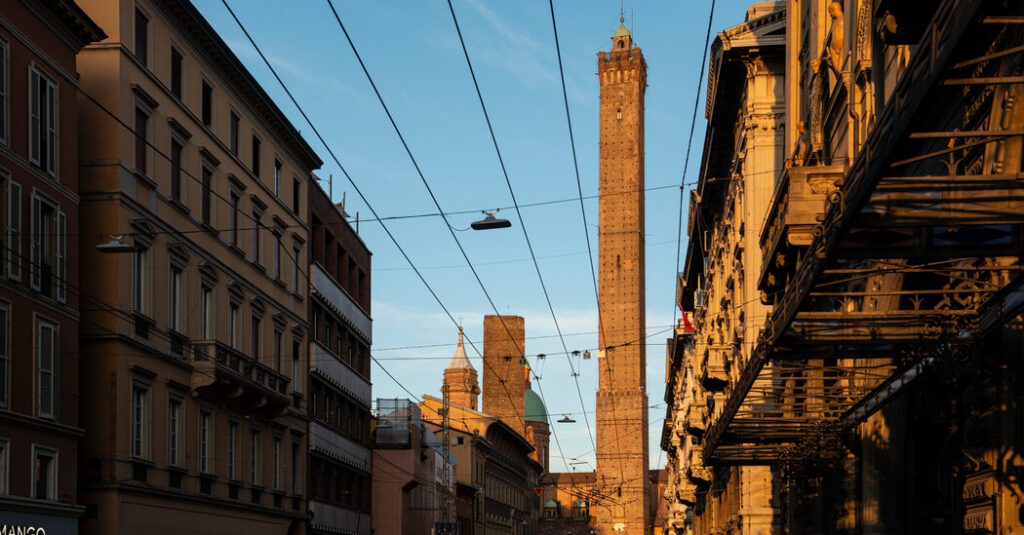

But it was also once medieval Manhattan, a city of towers (yes, that gave rise to the tower's other nickname, “La Turita”).

There were once around 100 towers, but most are now gone, having been cut down over the centuries or incorporated into palaces and modern buildings. Of the 20 or so that remain, Garisenda and its much taller neighbor Asinelli form the focal point of a well-preserved medieval city centre.

A treasured symbol of the city, the tower can be seen everywhere: on postcards, souvenir magnets, and even a giant chocolate Easter egg with a picture of the tower on the marzipan surface.

Built in the 12th century by the Garicendi family, a wealthy local family, the Leaning Tower began to lean during construction and was shortened by about 40 feet in the 14th century due to fears it would collapse. After centuries of exposure to the elements, he experienced considerable wear and tear, including two major fires. For at least 250 years, blacksmiths used forges built within the base of the tower, which severely degraded the brittle selenite stone at the base. This forge remained in operation until his late 19th century.

Modern concerns about the tower's stability began about 25 years ago and have been closely monitored ever since.

Engineer Raffaella Bruni, head of the expert committee tasked with preserving the tower, said efforts were intensified about five years ago when it became clear that “the pace of deterioration was accelerating.” said that it was done. As of 2021, the base is surrounded by thick steel cables and wooden planks (pictured with oversized orthodontic appliances), and dozens of sensors and other monitoring equipment that now detect even the smallest changes. It has become.

Currently, safeguards in place keep visitors approximately 65 feet from the base of the tower.

After a recent fact-finding trip to Pisa, the expert panel determined that the same system could be used with some modifications and decided on the pylon system. If all goes well, the pylon should be completed within six months.

Massimo Majowiecki, a Bologna-based engineer who worked in Pisa and is now part of the team in his hometown, said the work carried out on the tower in Pisa has extended its expected lifespan by another 300 years. The cost of maintaining Italy's vast cultural heritage is “a huge burden, but it also creates a lot of experience,” he said.

There is no way to tell if the Bologna intervention will work or for how long, but engineers hope computer modeling will help. A team at the University of Bologna is developing a digital twin for Garisenda to simulate the impact of potential modifications.

For now, the local community seems largely optimistic, despite media reports questioning the tower's stability.

Garisenda “has been through a lot, but it has never collapsed,” said Maurizio Pizzilani, whose wife owns Hotel Garisenda, a small inn overlooking the tower.

He said the hotel's website, which is currently receiving significant traffic, is equipped with a 24-hour webcam installed outside the hotel's breakfast room window overlooking the tower, allowing people to see what's going on at work. This is because they are being monitored. (Three towers were demolished decades ago to make way for the building of which the hotel is part.)

Like other local residents, Pizzirani had an opinion on the best course of action to take (starting with rerouting motorcoaches), but admitted that the tower “didn't have an instruction manual”. Ta.

Whatever the final solution, the tower work is expected to be too expensive for local governments to handle alone.

A fundraising campaign promoted by Bologna City Hall reminds people that the tower is part of the city's history and says: “Now you can be part of it too.” A city spokesperson said the campaign has raised 4 million euros ($4.3 million) so far, which has covered the costs of the campaign so far. The Italian Ministry of Culture has set aside an additional 5 million euros for the restoration, and the local government will also cooperate.

In the coming weeks, rockfall nets will be installed at the base of the Asinelli Tower and the tower in front of the adjacent Baroque Basilica of St. Sainte. Bartolomeo and Gaetano minimize the damage caused by the collapse.

The church is most at risk, but a recent visit inside found no evidence that the priests were planning for the worst.

“We have no special know-how in this area, so we will follow what the city hall says,” said the cathedral's parish priest, the Reverend Stefano Ottani. “We have not been told to restrict access to the cathedral or close it, so we are keeping it open.”

Engineer Bruni gave a different explanation. “They have great faith in the Lord,” he said with a smile.