Ten years ago, this was a big hole in the ground behind a home improvement store in Row, southern New Jersey.

However, 66 million years ago, when the dinosaurs became extinct, and many sea creatures died here, and sank to the shallow sea bottom of the time.

Due to the possibility of a prehistoric past, the former quarry hole has become the Edelman Fossil Park & Museum due to its past as a mass extinction cemetery.

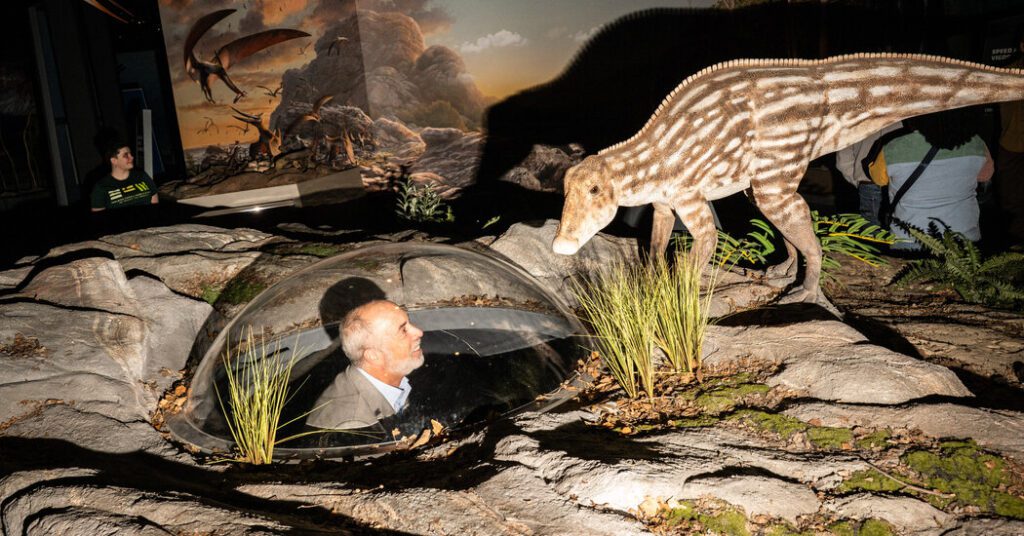

Built in Mantua, New Jersey, about 20 miles from Philadelphia, the museum welcomed its first paid clientele last weekend. For Kenneth Lacobala, professor of paleontology and geology at nearby Rowan University and executive director of the museum, it is the culmination of a decade of work.

“We do a lot here and I don't think it's been done at any museum,” said Dr. Lacobala, best known for paleontology for the discovery of one of the biggest dinosaurs ever, the Dreadnought.

The fossil comes with a difficult message from Dr. Lacobala, creating a direct link between the mass extinction 66 million years ago and today's rapidly changing climate.

The museum's motto is to “discover the past and protect the future.”

“It's really the thrust of this place,” Dr. Lacobara said. “We need to act, we need to act now, and every day we retreat, or worse, our retreat is a burden we place on future generations.”

For decades, the company scoops out of the quarry for dark greenish sand called Marl, which is used to treat water and soil. Environmental regulations became stricter, and the site turned into money losers, and instead tried to close it.

Mantua wanted the developers to turn the pits into more suburban homes and shopping. However, the Great Recession halted those plans and the quarry remained a hole in the ground.

Marl's mining exposed prehistoric sediments that spanned this whole region of South Jersey, but are usually buried underground at more than 40 feet.

At the time, Dr. Lacobara had begun visiting sites containing fossil-containing layers that appear to coincide with mass extinctions 66 million years ago. The conditions required to preserve bones are rare, so fossils that died on the day are scarce within the extinction layer.

“This is something I personally look for, and many other paleontologists all over the world,” Dr. Lacobala said, adding that he was looking for such a layer in southern Patagonia, including the Himalayas hills.

“And I found it behind the Row in New Jersey,” he said.

Over 100,000 fossils representing 100 species have been carefully excavated and cataloged from the quarries.

Until the pandemic, the site was open to the public once a year for community fossil excavations, allowing people to collect fossils from sediments above the mass extinction layer.

Rowan University bought the site for just under $2 million in 2015, invited Dr. Lacobara, who graduated from school while known as Glassboro State University, to join the faculty as dean of a new school for the Earth and the Environment. Rowan was also acquired by Dr. Lacobara's vision to build a museum.

“This will be a place to motivate young minds to become scientists,” Rowan president Ali Hausmand said in a statement at the start of the media tour.

Jean and Rick Edelman, the founders of the financial advisory company and alumni of the State of Glassboro, donated $25 million of the $75 million Rowan needed to build it.

“We quickly realized this could become a world-class destination,” Edelman said.

There are many things you'll expect to find at the Dinosaur Museum overlooking the fossil site of the Teacher Quarry. Near the ticket kiosk is the skeleton of a creature that lived along the eastern coast of North America during the Cretaceous period. The mosasaurus, a ferocious marine reptile, droops from the ceiling, and T. Rex's relative, Dryptosaurus, poses in horror.

The museum highlights how some of New Jersey's earliest dinosaur discoveries were created. The first almost complete dinosaur skeleton – the duck-covered hadrosaurus was excavated in 1858 at Haddonfield quarry. Dryptosaurus was the first Tyrannosaurus in 1866, just a mile away from the museum.

Visitors will walk along a winding path that passes through the museum's three galleries.

In the first gallery, the introductory film offers a perspective on how heart-wrenching our planet can be.

If the Earth's 4.5 billion years of history is a 1,000-page book, then the entire human civilization of 10,000 years is covered in just the last words on the last page. That sense of “deep time” is intended to set visitors to understand how the Earth's climate is changing unnaturally now.

A life-size recreation of a large, not-large dinosaur fills the gallery. In late Cretaceous warmth, sea levels were much higher and North America was a series of islands. For one thing, the food of a large, angry plant known as Astrodon dies by stomping on the Acrocanthosaurus, a boy's meat eater.

“We want to show you the rough belly of the dinosaur world,” Dr. Lacobara said.

The next gallery highlights marine life that lived in the ocean here, including sea turtles, sharks and saber-toothed salmon. This part of New Jersey was about 70 feet underwater and 15-30 miles offshore. “In this gallery, everything you see here is found on the premises,” Dr. Lacobara said.

That includes the scary Mosasaurus.

““I think it's statistically almost certain at some point that Mosasaur of this size was in that exact location.”

Visitors then enter the Hall of Fame of Extinction and Hope. It shows that the asteroid enveloped the Earth, which was enveloped after it struck the Gulf of Mexico from the Yucatan Peninsula.

Then it changes to the present. Other scientists describe it as the sixth extinction as the species struggles to adapt to changes humans have made to planets, including habitat destruction and global warming, which spurred an increase in greenhouse gases released from burning fossil fuels.

One interactive exhibit has shown a sharp rise in earth temperature over the past few centuries, allowing visitors to compare the curve with natural causes such as day spots, volcanic eruptions and periodic changes in Earth's orbit.

“None of these explains temperature fluctuations,” Dr. Lacobala said.

But simultaneous rises in temperature and greenhouse gases are “almost accurate correlations,” he said. “At that point you can draw your own conclusions.”

He said he wanted to look up the data himself and learn from people. “Not everyone connects the dots,” Dr. Lacobara said.

At the last station, the kiosk will inform visitors about how to take action to offset climate change. “Hope without action is truly despair,” Dr. Lacobara said. “Before you leave the museum door, you're all set to bring about positive change in the world.”

How will this message be played in an age when President Trump calls climate change a hoax and his administration is dismantling projects and research aimed at moving away from fossil fuels?

“I think we'll see when the museum opens,” said Kelly Stotzel, managing director who oversees the museum's day-to-day operations. It is expected to attract 200,000 visitors a year.

She said she was interested in hearing the reaction of visitors skeptical that the planet is experiencing rapid changes.

“When they come in and learn science, can you be sure they think of something different?” Stotzel said. “perhaps.”

For Dr. Lacobara, the message is simple. “You can't love things you don't know,” he said. “And we want people to fall in love with this amazing planet we have and make sure they take action to protect it.”

The museum's learning-by-learning spirit allows visitors to become paleontologists for a day. For an additional fee from May to October, visitors can dig into the sand of the quarry and dig fossils that can be taken home.

The museum also includes fun prosperity. Take an elevator between the second floor and you can hear that the name Dino is just like Dean Martin, as is the snippets of popular singers from the 1950s and 1960s. Therefore, “Dino Lounge” music.

At the entrance, “The facility is smoke-free, has no weapons, no asteroids (the past 66 million years) is free.”

Dr. Lacobara is proud of the glass used in exterior windows. Because modern dinosaurs – birds – are flying deadly.

“What I really like is that it relies on evolutionary principles,” Dr. Lacobara said.

The first vertebrate eyes, preceded both mammals and dinosaurs, had four color receptors for red, blue, green and ultraviolet rays.

Birds, dinosaurs that survived mass extinction, still carry UV receptors in the eyes. They fly safely away when they see images of spider nets engraved on the museum's glass.

“You come out and you catch a right angle and you can see it,” Dr. Lacobara said.

However, mammals have lost the ability to see ultraviolet rays. Because when they happened over 200 million years ago, they were little creatures that ran around at night. There is not much UV rays at night. In mammals, genes employed by the olfactory system to locate the receptors of the eye.

As a result, mammals tend to have a good taste and smell, but they cannot see UV rays.

“To our mammals, this looks like clear glass,” Dr. Lacobara said. “And I know this because the driver of the forklift truck that went through one of these panes was a mammal.”

With the museum now open, Dr. Lacobara wants to turn his attention to proof that the mass deaths of the quarry consisted of animals that were actually killed in the planetary cataclysm following the asteroid strike.

However, it was difficult to settle as creatures digging holes in the seabed stirred up the sediments. As a result, markers of extinction – layers containing a substantial amount of iridium, an element enriched by asteroids and comets – are ambiguous.

“It's like looking at something at the shower door,” Dr. Lacobara said.

He said he had all the data he needed, but even working at the museum he hadn't finished his time writing his paper.

“All this has been consumed,” Dr. Lacobara said.